Key Points

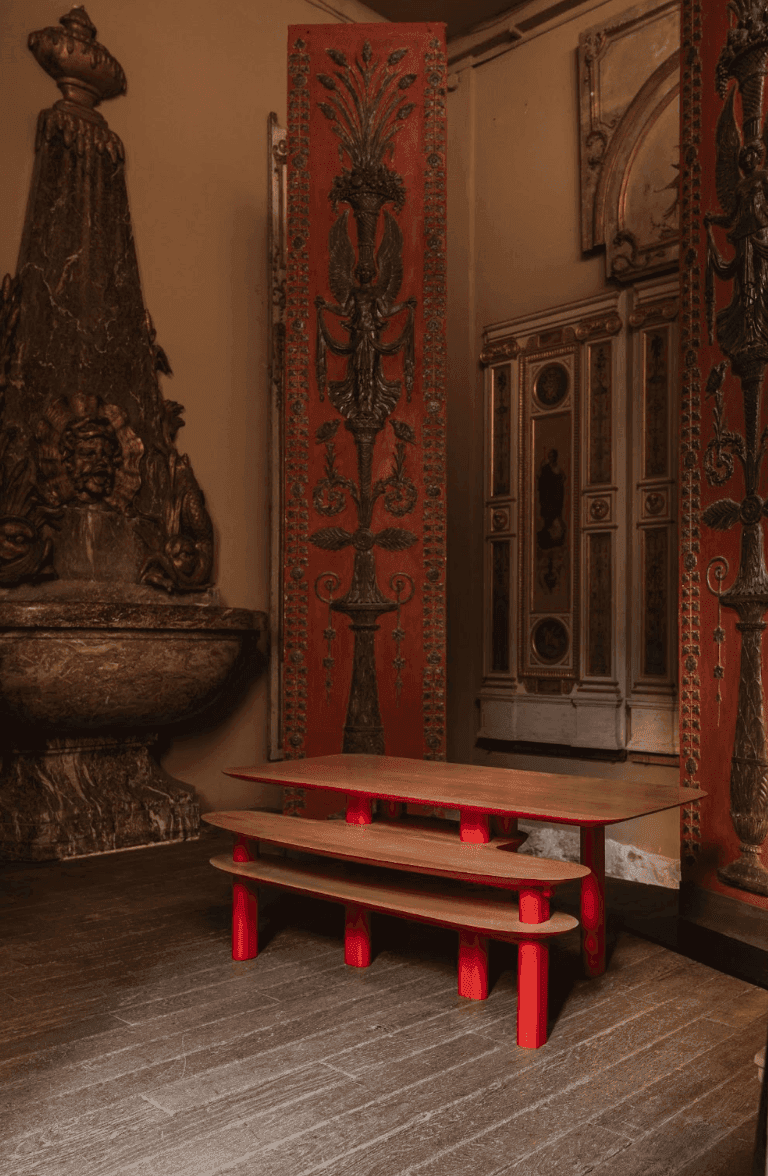

- Torii Table: Solid beech sourced <100 km from Paris, fully traceable; 12 layered colours revealed through wear; demountable and repairable.

- Circular chair concept: Chaise qui cache la forêt uses only natural, biosourced inputs with end-of-life return to nature; seeds embedded in legs reinforce the narrative.

- Silk lighting: La lampe qui va de soie uses Cévennes non-woven silk from Sericyne; modular form (wall/table/pendant) balances variability with durability.

- Process discipline: Early, holistic brief maps material origin, embodied impact, end-of-life, and supplier capability to ensure industrial reproducibility.

- Supply chain reality: Regional/artisanal sourcing faces seasonal cadence (e.g., sericulture); output scaled by embracing slower, high-craft production.

Full interview with Julien Gorrias

1. In your recent project of the table “Torii Table”, how did your “positive design” philosophy influence the selection of material up front, and what properties were most decisive in choosing it?

For the Torii Table, my idea of positive design lies less in ornament and more in the relationship between time, material, and emotion. The table is crafted from solid beech wood, carefully selected for its grain and compatibility with the machines that shape it, and sourced less than 100 kilometers from Paris. The wood is fully certified and traceable throughout the supply chain, an ethical foundation for a piece made with the utmost material integrity.

Upon this structure, I applied twelve successive layers of paint, each a different hue. The chromatic sequence is inspired by a Hasui Kawase print depicting a torii, a serene Japanese landscape from the shin-hanga tradition. These hidden colours lie quietly beneath the surface, waiting for time to reveal them. As the table is used, through contact, touch, and wear, new tones gradually emerge, like memories surfacing through experience.

In this way, positive design becomes an attitude toward time itself: wear as revelation, aging as beauty. The more the table lives, the more colourful it becomes, gaining emotional value through a process of benevolent erosion. The piece does not resist time; it collaborates with it.

The table is fully repairable, demountable, and designed to last, allowing future maintenance or component replacement without compromising its integrity. Together, the solid beech and layered paint embody both precision and poetry, a structure rooted in the French landscape, yet animated by the distant light of Japan’s prints and the symbolic presence of the torii.

2. For your piece “Chaise qui cache la forêt”, which you presented in 2023, could you describe how you treated material traceability and what supplier documentation you required to validate its ecological credentials?

The Chaise qui cache la forêt was conceived as a question: can a chair be modern, desirable, industrially producible, and yet entirely made from natural, biosourced materials? This piece is a direct exploration of that challenge.

Its name reflects its essence: the chair is so composed of natural matter that, if one ever wished to no longer use it, it could almost be returned to the forest. In keeping with this vision, seeds of flowers and trees are hidden within its legs, giving the chair the potential to restore to nature what it originally drew from it.

Every material was selected not only for performance: structural integrity, comfort, durability, but also for its ecological logic and traceability, ensuring that the chair remains elegant, functional, and industrially reproducible, while fully participating in a regenerative cycle. In this way, the chair embodies a design that is both desirable and deeply responsible, a dialogue between human use and natural return.

3. In the lamp “La lampe qui va de soie”, handcrafted in the Sericyne workshop (Cévennes), which material challenges did you face, for example variability, durability, modularity, and how did your process evolve to overcome them?

La lampe qui va de soie was born from the encounter between light and silk, a natural, living material handcrafted in the Sericyne workshop in the Cévennes. This project was guided by the aim to create an object that is aesthetic, durable, and modular, while fully respecting the specificities of silk.

Silk is an organic material, with each thread possessing unique characteristics. This variability can create subtle differences in texture and color, making each piece unique. To embrace this variability, we adopted an artisanal approach, allowing us to highlight and celebrate the natural imperfections of silk.

Silk’s durability is another challenge. Although natural, it is sensitive to environmental conditions. To ensure the lamp’s longevity, we collaborated closely with the Sericyne workshop, which uses a specialized non-woven silk process that improves resistance and dimensional stability.

Modularity was essential to allow the lamp to adapt to different spaces and uses. We designed a lightweight, flexible structure, enabling it to function as a wall sconce, table lamp, or pendant, depending on need. This flexibility is made possible by the silk’s ability to retain its shape while offering gentle suppleness.

The creation process evolved in close collaboration with Sericyne, whose expertise in sericulture and silk processing allowed us to overcome the challenges of material variability and durability, while respecting the principles of local craftsmanship and responsible production.

4. When you envisage a material-led concept at the earliest stage, how do you engage suppliers, or material-intelligence tools, to map availability, environmental data, for example embodied carbon, end-of-life path, and commercial scalability for the product?

It is crucial, from the very beginning of a project, to clarify an extremely detailed brief, especially when it concerns the material of an object. It is the material itself: its method of production, its transportation, its distribution, that will shape the project. There is a deep interdependence between the object as a whole, the material it is made from, the place where it will be sold, and the way it will be used.

In fact, it is a bit like a Rubik’s Cube: you cannot complete one face without considering all the others. You have to work on all the faces simultaneously. This is essential, and it is often the client’s ambition that drives this approach, because it is always easier to take shortcuts and go faster. Here, however, one must map everything, create a coherent logic throughout the process, and embrace the complexity from the start.

5. Looking at the Chaise qui cache la forêt, which uses a narrative of nature and hiding, how did the narrative or aesthetic intention influence technical decisions on materials, texture, finish, sourcing, and how did supplier capabilities factor in?

The way a project is conceived at Carbone 14 Studio follows a holistic approach. In the case of La Chaise qui cache la forêt, everything begins with the framework defined at the outset through the list of constraints. The name, the object, the materials, and the manufacturing processes are all connected by a single guiding principle: the pursuit of coherence.

In this instance, the chair draws its inspiration from the wood of the forest and was designed from the start with a strict commitment to using only natural materials in their simplest form, so they could one day return to nature. The object was conceived from the beginning with its end of life in mind.

The chair was meant to be crafted by a cabinetmaker’s hand, that was the starting point. Wood was an obvious choice: it had to be local, sourced within 100 km of Paris. All these decisions came together quickly, creating a project whose various threads converge into a logical and coherent whole.

6. With regional or artisanal suppliers, for example, the Cévennes-based Sericyne workshop used for the lamp, what are the key supply-chain constraints you encounter when moving from prototype to production, and how do you mitigate them?

The greatest difficulty I encounter in the supply chain lies in the smooth coordination between the different stages: the commercial side, production, and procurement. This challenge is even greater when working closely with nature, using bio-based materials. For example, with the lamp, the silk sourced from the Cévennes is naturally tied to seasonal cycles: silkworms feed on mulberry leaves, the mulberry trees need to grow, and the silkworms require certain temperatures to thrive.

These constraints are not always aligned with commercial rhythms, which follow purchasing patterns and momentum throughout the year rather than the seasons. Today, my way of managing this is to focus on each piece as unique, embracing almost an appreciation for slowness. Too often, there is a desire to have everything immediately, but I believe we need to return to a mindset that values the awareness of each object, taking the time to acquire an extraordinary piece that requires a proper period for its creation.