Key Points

- Separate roles in the stack: glass handles optics and tactility; aluminium handles structure and heat. This layered approach lets you swap or update LEDs and drivers without redesigning the craft component.

- Use optics, not electronics, to create “signature” effects: the inverted “Z” pattern comes purely from refraction between 4 LED strips, a diffuser tube and knurled glass, showing you can get distinctive light behaviours without custom LED hardware.

- Flip the brief: in the Ray collection, the project starts from PCR extruded aluminium as the non-negotiable and then finds products (speaker, clock) that fit the process, a useful model for making recycled materials the baseline rather than the compromise.

- Assume tech is fast, craft is slow: LEDs, Bluetooth and drivers are now small and standardised, so the real design work is engineering variance, cost and rejection rates if you want artisanal processes (like Murano glass) to survive inside industrial supply chains.

Full interview with Neil Poulton

1. What properties of mouth-blown Murano glass, particularly using the Venetian “balloton” technique, made it especially suitable for achieving both texture and light diffusion in the Alambicco lighting modules?

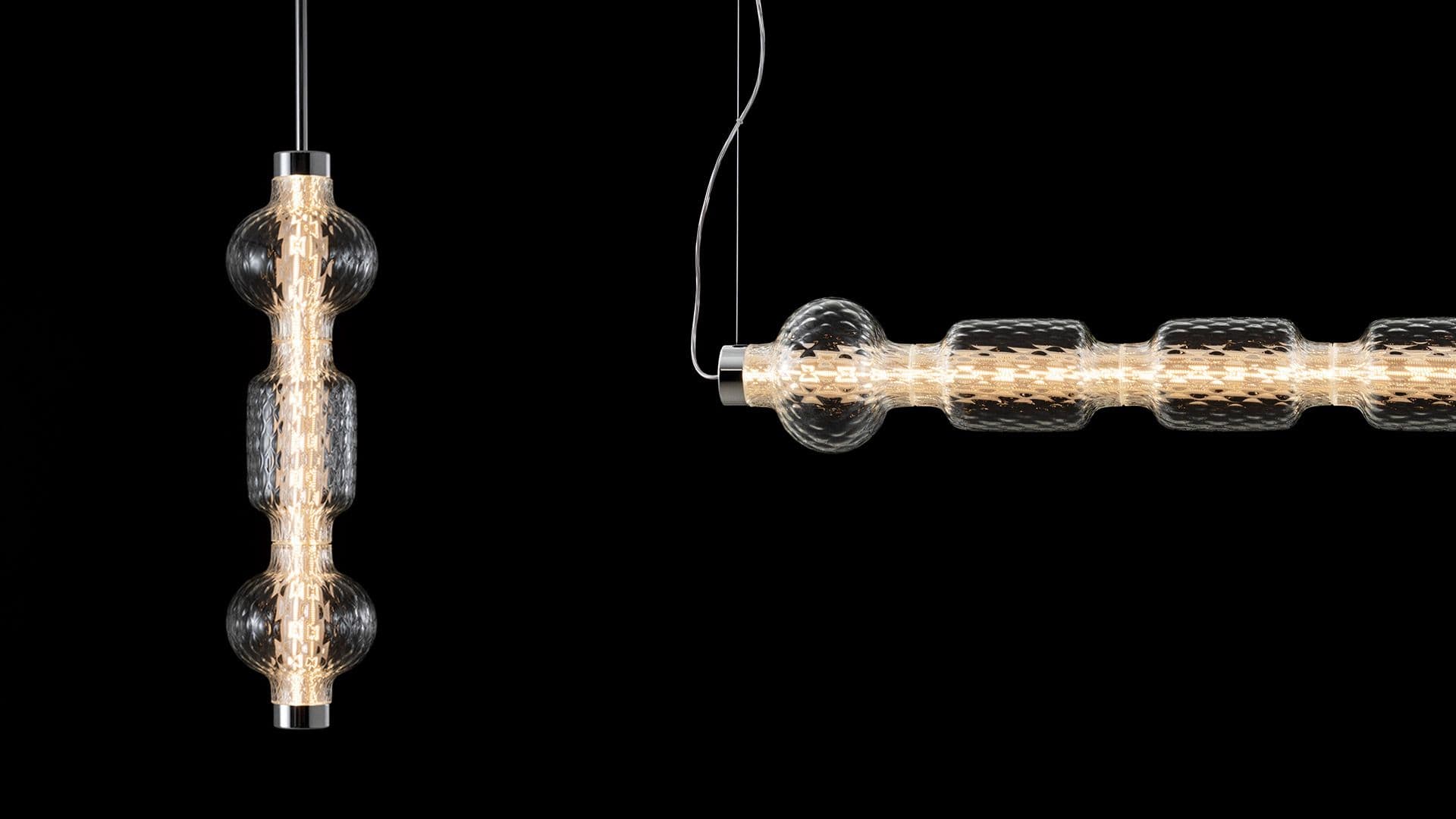

“Alambicco” wasn’t always a “balloton” glass project. I originally imagined a modular ‘abacus’ system, constructed from glass modules threaded on an LED tube. These had a complex, laser-engraved subsurface pattern, stunning in renders, difficult in reality. Daniel at Artemide suggested exploring “balloton” glass instead and brought it to their Murano facility for sampling.

The “balloton” technique preserved the spirit of the original vision while adding a rich texture and light-diffusing depth. It also meant the modules had a strong visual identity even when the lamp is off.

2. When integrating glass modules onto an extruded aluminium LED structure in Alambicco, what technical challenges did you face in terms of thermal behaviour and assembly tolerances?

Each module is mouth-blown, meaning no two are identical. We deal with tolerances of +/- 1–2mm in diameter and texture, so precision stacking was impossible.

To solve it, we used flexible silicone joints to absorb dimensional slack and isolate glass pieces from mechanical stress. The aluminium core handles heat dissipation, and since the drivers are ceiling-mounted, thermal issues were minimal.

3. The name “Alambicco” (alembic) evokes distillation. How did that concept influence the modular design logic and material layering in the fixture?

Carlotta coined the name once she saw the prototype. It gave us a retroactive narrative hook, whisky bars, illicit stills, prohibition-era lighting, etc. That storytelling helped shape the commercial identity and emotional tone of the piece.

4. Could you explain your decision to reveal, yet softly refract, the embedded LED core through the knurled glass? Was that balance of concealment and exposure deliberate for a poetic effect?

I'd like to claim poetic intent, but it was a lucky accident. The repeating “Z” pattern emerged from the way the diffuser inside the glass interacts with light. Four internal LED strips sit in a cylindrical diffuser, and when viewed through the refraction of the blown glass, they generate that optical zigzag. We didn’t plan for it. It only revealed itself at the prototype stage, and only as you approach the lamp.

5. With Alambicco offering both horizontal and vertical compositions, how did the orientation affect the structural design of the aluminium frame and the ergonomics of the glass modules?

It’s all about load management. Horizontal builds spread the weight between two suspension cables. Vertical stacks rely on one load-bearing tube, so sway is a factor. The floor-standing version is all compression-based. The central aluminium spine is critical. It anchors and aligns everything.

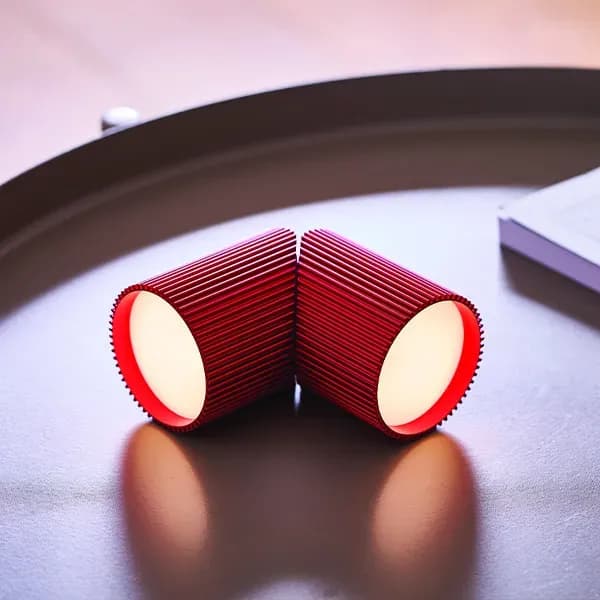

6. Turning to the Ray Collection, what made extruded aluminium the material of choice for both aesthetic coherence and functional durability in the speakers and the alarm clock?

When I first pitched to Lexon, I presented themes rather than designs, blurred atmospheres, recycled aluminium textures. From there, we developed a collection of unformed ideas around PCR aluminium. So, the material came first, the objects followed.

I try to avoid virgin plastics. I push for recycled (PCR) and recyclable materials. But convincing high-volume manufacturers is tough. PCR is often pricier, and clients complain about inconsistencies and defects.

7. Both the Ray Speaker and Ray Light employ magnetic, respectively Bluetooth and LED, technology. How did the demands of wireless electronics influence material selection or form-finding?

Honestly, not much. Today’s wireless tech is compact and self-contained. It rarely dictates form unless you're designing something extremely small or electromagnetic-sensitive.

What did matter was the sound. The Ray Speakers offer an impressively wide soundstage given their size, thanks to TWS (True Wireless Stereo) tech. Bass is limited by driver size, but that’s physics.

8. Looking forward, how do you see the role of traditional artisanal techniques like mouth-blown glass being reconciled with scalable LED and electronic systems in future industrial design?

It’s about merging fast tech with slow craft. As a designer, I’m one piece in a chain. The magic happens when clients and partners are on board with handmade production that defies mass manufacturing.

With Alambicco, we embraced that contradiction, Murano glass meets modular LED. Every piece is unique. Imperfections become identity. I'd love to transfer that philosophy into other products and domains.