How does Fmt Estudio integrate the unique environmental characteristics of the Yucatán Peninsula into your architectural designs?

The Yucatecan landscape is defined instead by the dry and rainy seasons.

During the dry season, many trees lose their foliage, the dry branches barely produce any shade and the ground seems completely dry, increasing the feeling of heat in the already high temperatures. It is also during this time that many flowers bloom miraculously.

On the other hand, the rainy season creates an abundance out of the minimal presence of water. As the first tiny drops of rain touch the ground, they unleash a sudden revival: The dry branches of the trees become green with foliage again. Many grasses and wildflowers also sprout miraculously from the seemingly barren land. When the rain intensifies it can provide many cubic mm of water which sometimes can overwhelm gutters and absorption wells.

Although harsh, the cycle of the seasons, presenting the regeneration of the land, is quite impressive. That is why we aim to create comfortable places for contemplation of this and other phenomenon of the region such as the distinct sunsets, with their pink tones and gentle afternoon breezes, which are almost a reward for withstanding the hardships of midday temperatures.

The Yucatecan land is also very hard and very flat, as it is formed out of a giant limestone plate that allows a very thin layer of soil. Although minimal, this layer has incredible fertility providing sustenance for a great variety of flowers and fruits.

The approach in our practice is to provide consistent comfort during the two main seasons without relying completely on mechanical devices or technologies. This presents a hard challenge as we need two different things in our buildings: comfortable freshness during the dry season and protection from heavy rain and extremely sultry weather during the rainy one.

By local tradition, our relationship to the land is very grounded in life outside. The exteriors of a building are considered to be a part of our lives, as are the interior spaces. Mayan settlers used to play, cook, farm, and rest in these areas. Their houses were only built to store some items and have a protected area for sleeping. The exteriors were protected by large trees, providing comfort to sustain life, where many fruit trees were grown.

Taking a hint out of Mayan tradition, we strive to make outside livable, allowing us to experience the changing landscape and seizing the benefits of thermal comfort under tree canopies.

Since most of the vegetation is short and xeromorphic, large tree species that provide shade are of utmost value. Our buildings are placed in their surroundings with precise dedication, analysing the best possibilities to create a livable exterior in which terraces, walkways and other architectural elements are supported by the main architectural mass.

In city life we have forgotten about simple pleasures such as watching the rain, hearing the singing of the many birds, and smelling the sweet flowers and fruits. Many buildings have become devices to expel nature, rather than appreciate it. That is why, as architects, we strive to create a consciousness of our landscape and its very distinct features.

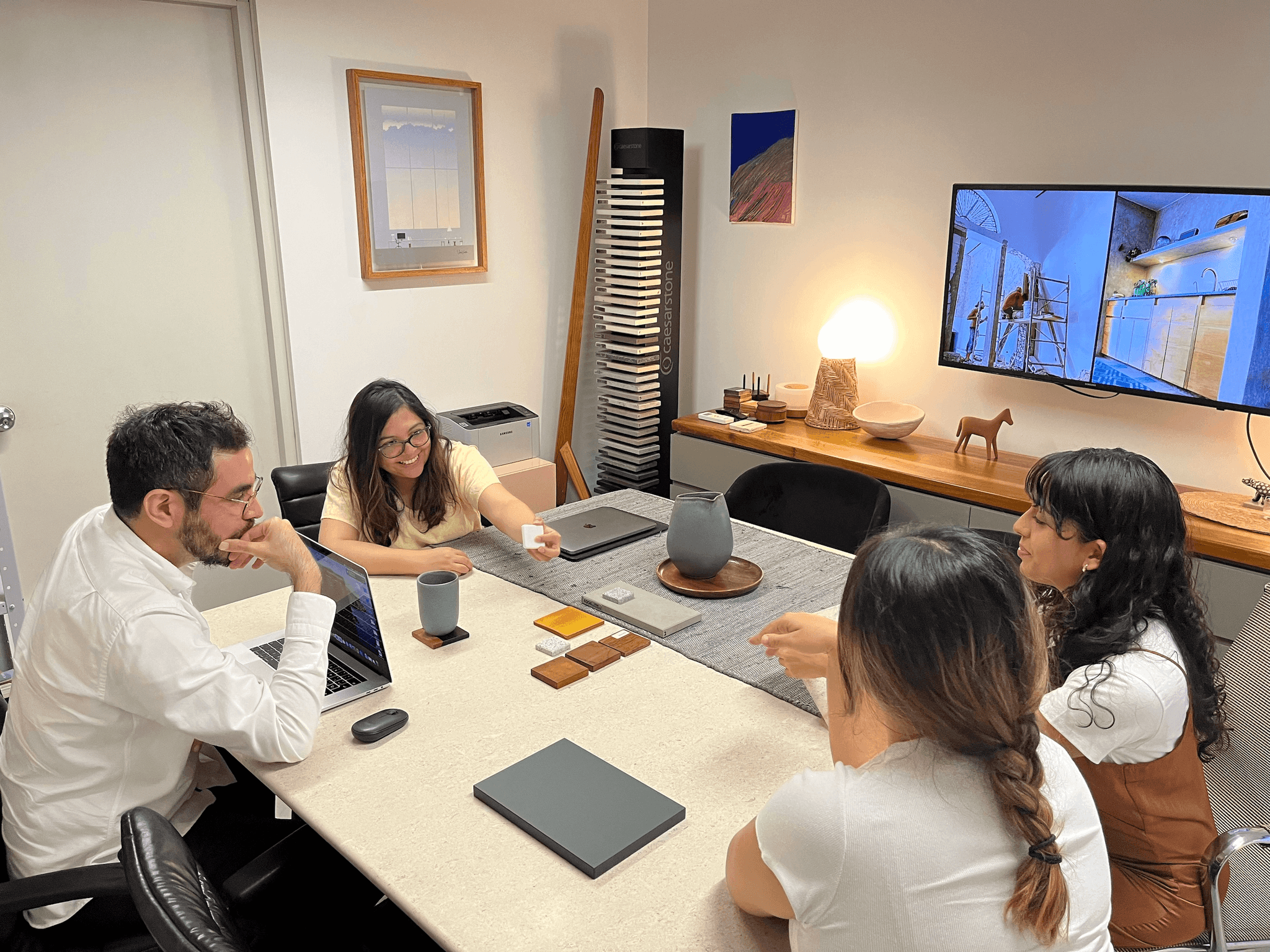

What methodologies do you employ to explore and select the most sustainable and aesthetically pleasing materials for your projects?

The materials in Yucatán degrade very fast. In an instant, the scorching sun can be interrupted by a fine drizzle that creates a compression and expansion that most building materials cannot sustain. This happens not only on buildings but also on roads and pavements which can enhance the feeling of heat due to sultry weather when a whole surface of concrete is poured into an area without any shade.

Another factor that contributes to the degradation of materials is the “heavy” water. This water has a very high concentration of minerals, such as calcium, that accelerates the corrosion process in metal structures and clogs pipes transporting it.

Oftentimes, top-grade materials from other parts of the world, developed for harsh environments, usually fail to stand the test of time in these conditions.

In Yucatán, the most commonly used materials for architectural mass are cinder blocks and limestone. When used properly those are capable of protecting the interiors and their contents, especially doors and windows that can degrade easily, if left unprotected.

Cinderblock is an industrialised material accessible everywhere around the state and is used for almost 90% of residential walls. Limestone is an abundant natural option, better overall for insulation and humidity control in walls, but needs to be manually transformed. Because of that, it is very expensive to build, and few buildings include limestone as a building material.

Amongst other popular choices for new, natural, locally sourced materials we can find palms, clay and “bajareque” (a young tree trunk) used in traditional Mayan houses.

Those can be used in other structural elements besides walls, but their lifespan is not comparable to the aforementioned. They are also incapable of harbouring contemporary installations such as wiring, plumbing, or optic fibre. The challenge with these materials is to create a standardised version of them to make them accessible. This requires significant research in labs and universities; as we need to stabilise them for the building process.

The main structure of a building is composed of a beam and truss industrialised system and cinderblock. At present, there has been no sign of a material innovation or technology in the region that surpasses the convenience of this system. In the past years, there have been several material options introduced, but they usually come with a high-carbon footprint and cost due to importation. Considering that, we focus mainly on research for new architectural finishes.

The main qualities of those materials are durability, heat gain and capillarity; all related to heat transfer onto our buildings. This is especially relevant in the presence of our sultry weather. Materials with the most resistance to bouncing light and resistance to harbouring humidity are chosen.

The method employed for researching new ones is very simple. We test them by leaving them for one week in direct sunlight to understand their behaviour. Sometimes we measure their temperatures. If they can withstand degradation and corrosion, we choose them and proceed to work around the details of how to transform the material. Although straightforward, this method has proven to be successful, since the materials that are being researched, do not pose threats to the safety of the inhabitants, and thus, don’t require lab testing.

Door and window systems are also researched, but the focus on them is mostly to ensure that the hinges and mechanisms present in them can be maintained with ease.

How do you approach the challenge of maintaining the cultural and historical integrity of spaces while introducing contemporary architectural elements, especially in remodelled houses with history?

When facing remodelling in a historical context, we always pay attention to the conditions that make the building unique. This, in most cases, is an architectural element or a material feature that serves as a “witness” of the history of the building.

This strategy is mainly due to clients’ requests. Many of them require implementing contemporary technologies onto historical buildings which makes the process very invasive to those existing structures. The historical preservation of the building in this context can be very difficult. We take a significant amount of time to document it and create an emphasis on the main historical features.

Considering this, we believe that inevitable posterior additions should be notoriously different from the original building and should not create a sense of false history. Any new element, either integrated into the structure or creating a new spatial configuration should pronounce itself as a contemporary one.

These elements should communicate a sense of relation amongst the new and the old, and commit to a concept. That way, the building can still show part of its original history and show its additions properly.

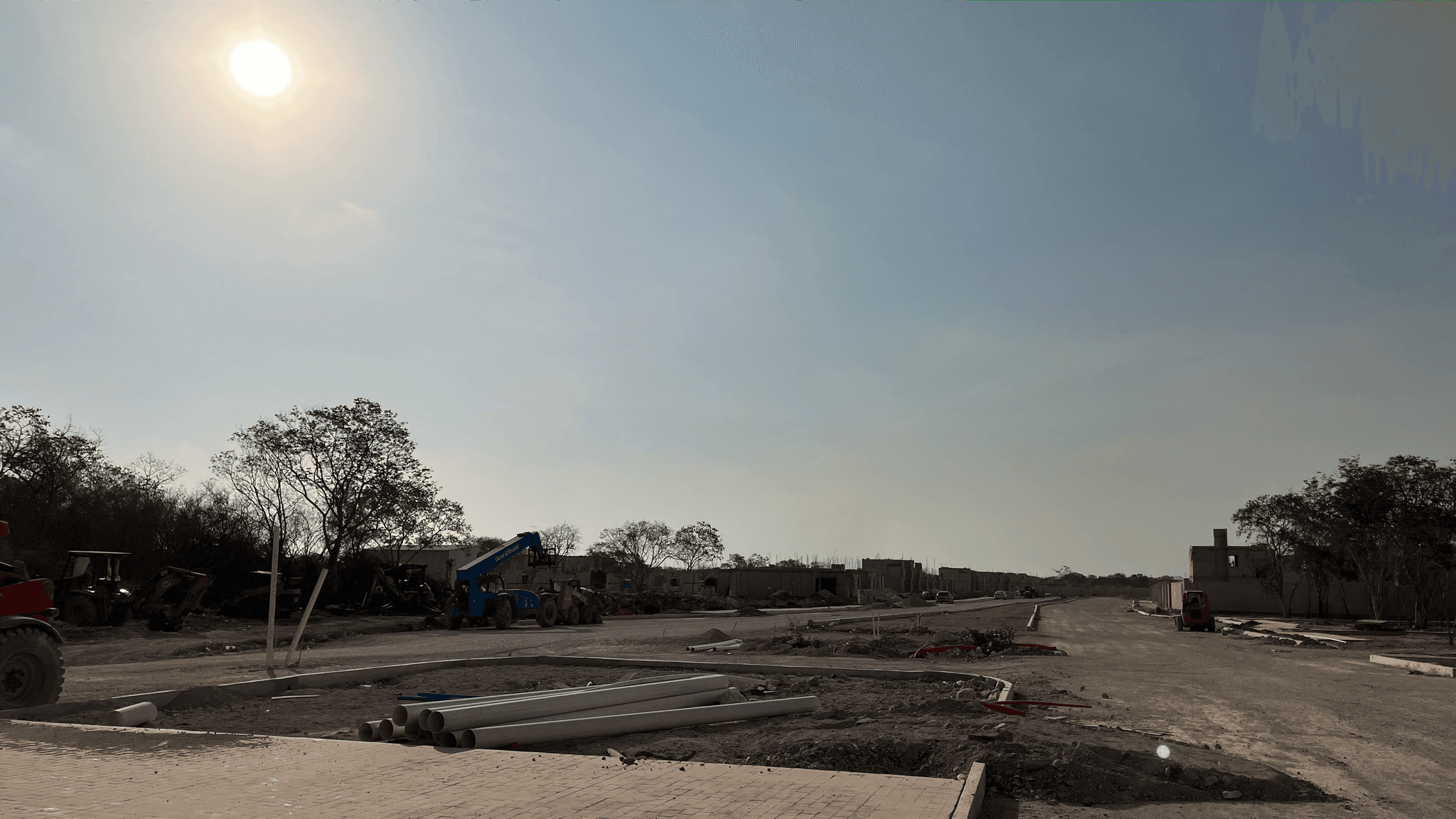

Could you discuss the importance of construction monitoring in ensuring the fidelity of the architectural vision from design to completion?

A project is a live entity that will develop with or without the presence of the mind behind its definition. Once it starts construction, things will happen very quickly, sometimes not even allowing ourselves to pay attention to important details.

It is widely known that a project will hardly finish the way it started, as it is a multi-layered reality that is created by many different hands and thousands of questions. The builder has its own set of goals; as so does the client, the plumber, the plasterer and the ironworker.

In allowing an architect to be the guide within the project, especially when it is the one creating the concept, we can ensure proper collaboration and communication between the different parties and achieve a defined objective. This also enables the opportunity to improve the project during the process.

How does FMT Studio navigate the budgeting process with clients to balance visionary design with financial realities, particularly in large-scale projects?

Budgeting usually establishes the ultimate reality of the project. When designing we always keep an eye on the discussed budget and the total square footage of the desired building to make sure that they are compatible, since the constructed area defines around 60% of the total cost. The rest is finishes, systems and other details.

The first step in this process is defining a budget. Transparency and trust are required from the client from the start, as communicating the real intentions of the project will provide clear goals and limitations to the architect.

The following steps are enlisting the desired spaces into an architectural program and discussing the scope of the project to adjust accordingly. We put a lot of effort into making sure that the client is aware of the preliminary amount of space that the original requirements will translate into.

It is possible to fine-tune the objective once the space requirements are set. This is achieved through choosing materials and accessories to complement the design.

In large-scale projects, in addition to the aforementioned, it is very important to address all of the steps and consultants required for the development of the project, as the building, or masterplan can involve much more decision.

In your experience, how has the architectural landscape of Mérida and the Yucatán Peninsula evolved over the last few years, and how do you envision its evolution in the future?

Historically Yucatán is known for having a very successful architecture scene. Many styles were developed and tested over the years: colonial, Porfirian, modern, postmodern; all of them with a strong sense of locality.

In recent years, architecture in Yucatán has developed alongside the region’s commercial and investment scenarios. Many architects and builders have thrived alongside this, dedicating themselves to large-scale tourism and real estate projects.

In some cases, offices have become real estate promoters of their own projects.

Currently, individual houses and public infrastructure are less prominent in the architects’ repertoire of projects. The landscape (a word less and less present in our language), is not being currently studied to be carefully framed by architecture, but rather being desertified in the name of the efficiency of subdivision of parcels. Every “empty” or “undeveloped” area is quickly occupied to be part of a commercial strategy.

This is very common around the world, but in Yucatán, there are no physical limits to the expansion and speculation of land. The laws are also very feeble, with little disposition to control the seemingly never-ending urban sprawl that’s causing severe landscape deterioration.

On the other hand, this scenario has created an opportunity for other architects seeking to establish, once more, a respectful conversation with the landscape. Architects that are manifesting against the former paradigm of “development”, and work on projects focused on defending the territory’s conditions. The belief that this speculative development scenario can’t last forever is also an important driving force in contemporary architectural practice, as we must be ready to address the issues of tomorrow.

As cities continue expanding, unaware of resources, it is important that new developments can implement careful strategies for the preservation of soil; especially in a country where water scarcity is a close possibility.

In the near future, as the population increases, we envision practices specialising in sensible solutions that tackle environmental issues, such as water treatment and a more developed thermal insulation approach. This will be observed more from an empirical perspective, learning from traditional practices and implementing them in a more contemporary context to provide long-term local solutions, rather than relying completely on technology; as technology oftentimes proves to be a temporary solution reclaiming from one side, to provide for the other.