Key Points

- Biomimicry as method, not motif: studies multi-scale natural structures to translate “form = function” into engineered products.

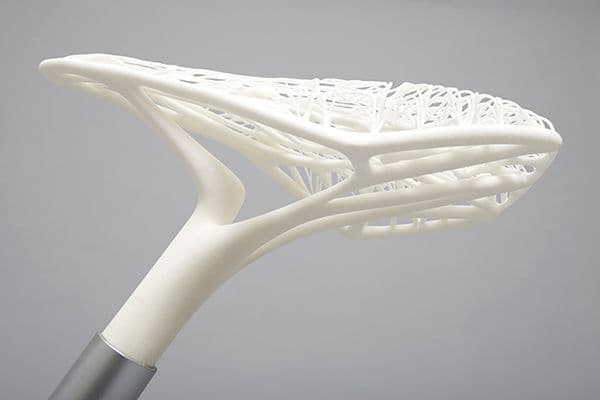

- Single-material, functionally graded designs: 3D-printed lattices tune stiffness/comfort (e.g., soft seating, bike saddles) via density gradients.

- Process is empirical + computational: rapid prototyping and physical testing first; selective use of topology optimisation/generative tools for refinement.

- Nature–tech balance: material/printing constraints (resolution, process limits) steer geometry; aesthetics remain integral to performance.

- Horizon: nanoscale AM and biofabrication (bacterial/fungal systems, structural colour) to enable responsive, possibly self-assembling, regenerative materials.

Full interview with Lilian van Daal

How do you identify which natural structures or biological processes to study for your projects?

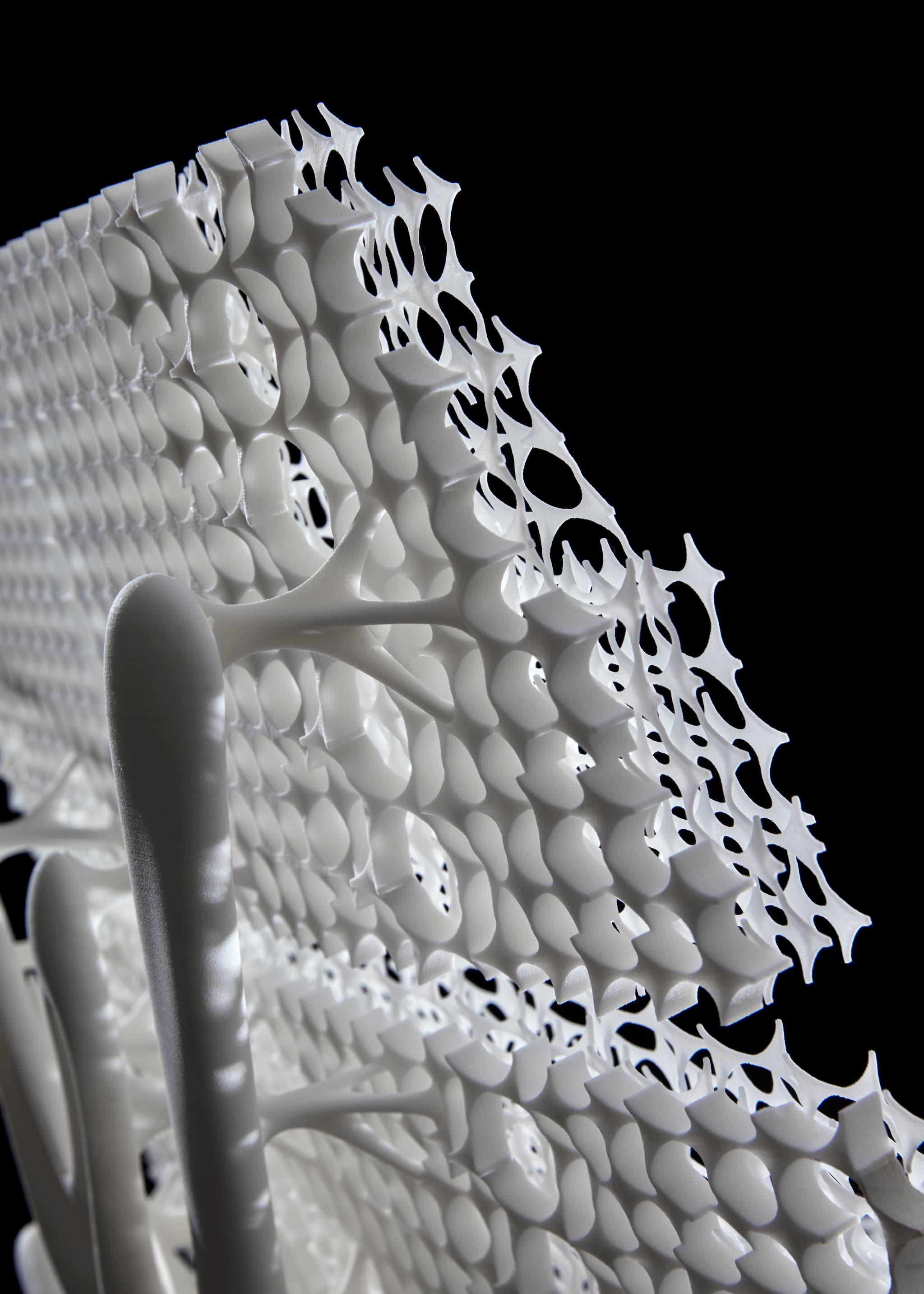

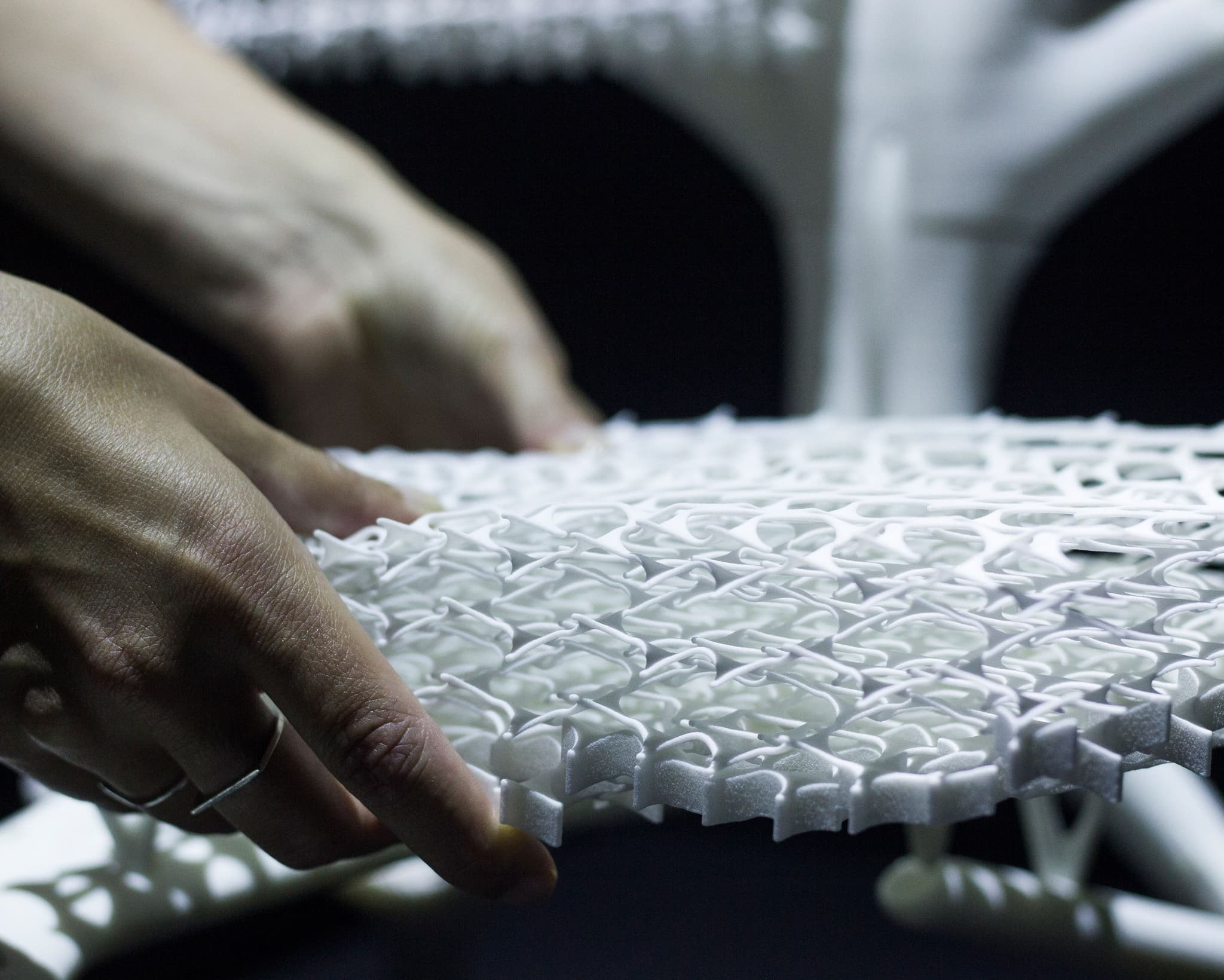

The selection of natural structures or biological processes to study is highly project-dependent. For example, my Biomimicry 3D Printed Soft Seat project originated from research aimed at making soft seating more sustainable by using a single material. In this process, I explored how to achieve specific properties, such as comfort and strength, by translating natural structures into 3D models and printing them from a single material. This type of research always begins with a literature review, consulting scientific articles, and closely examining both micro- and macro-structures in nature to understand how form dictates function.

However, sometimes a project is sparked by a fascination with nature itself. For instance, I have studied natural light phenomena and explored how they can enhance lighting design. By observing how fish scales reflect light, I investigated ways to improve lighting efficiency in our environments.

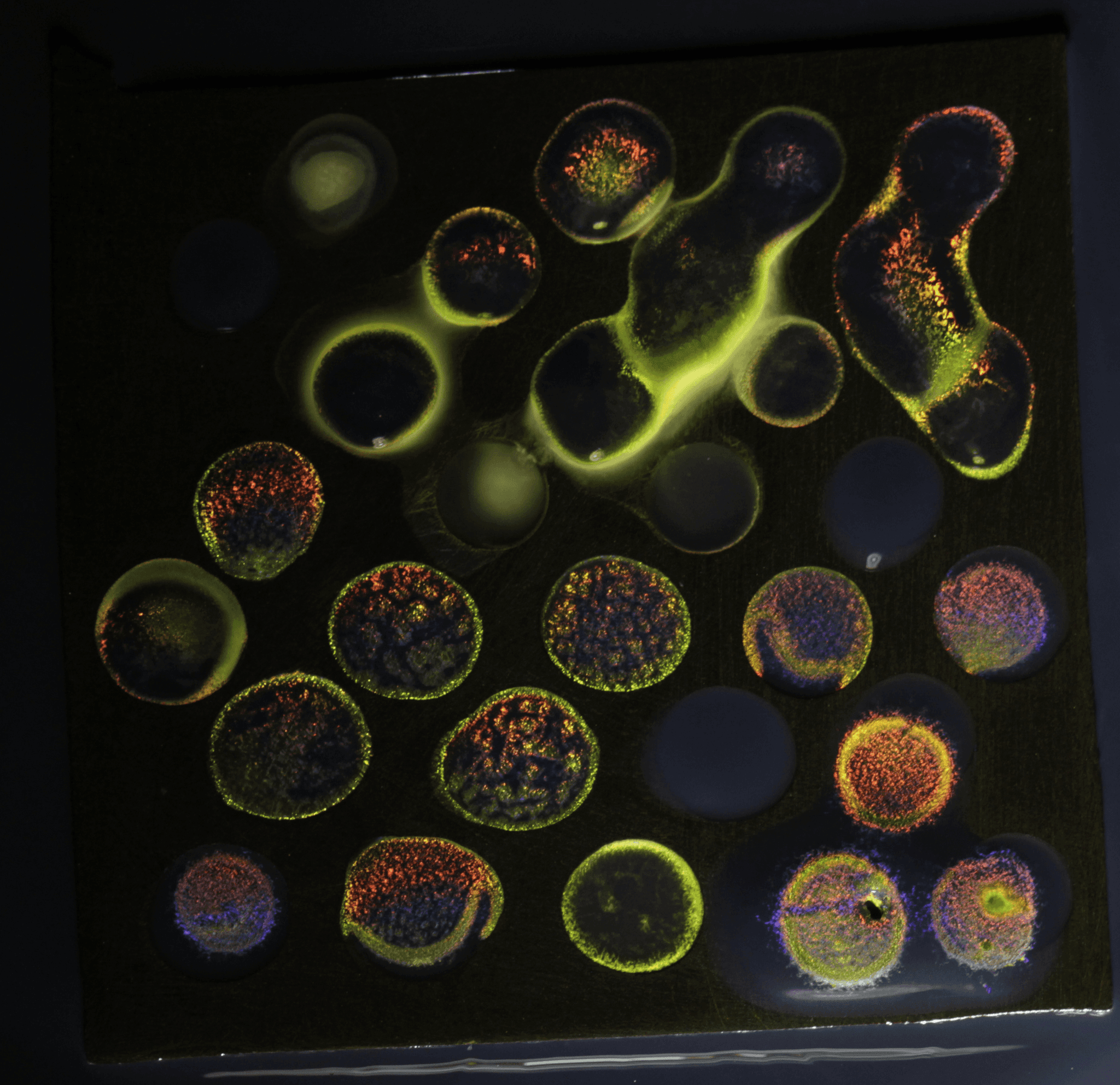

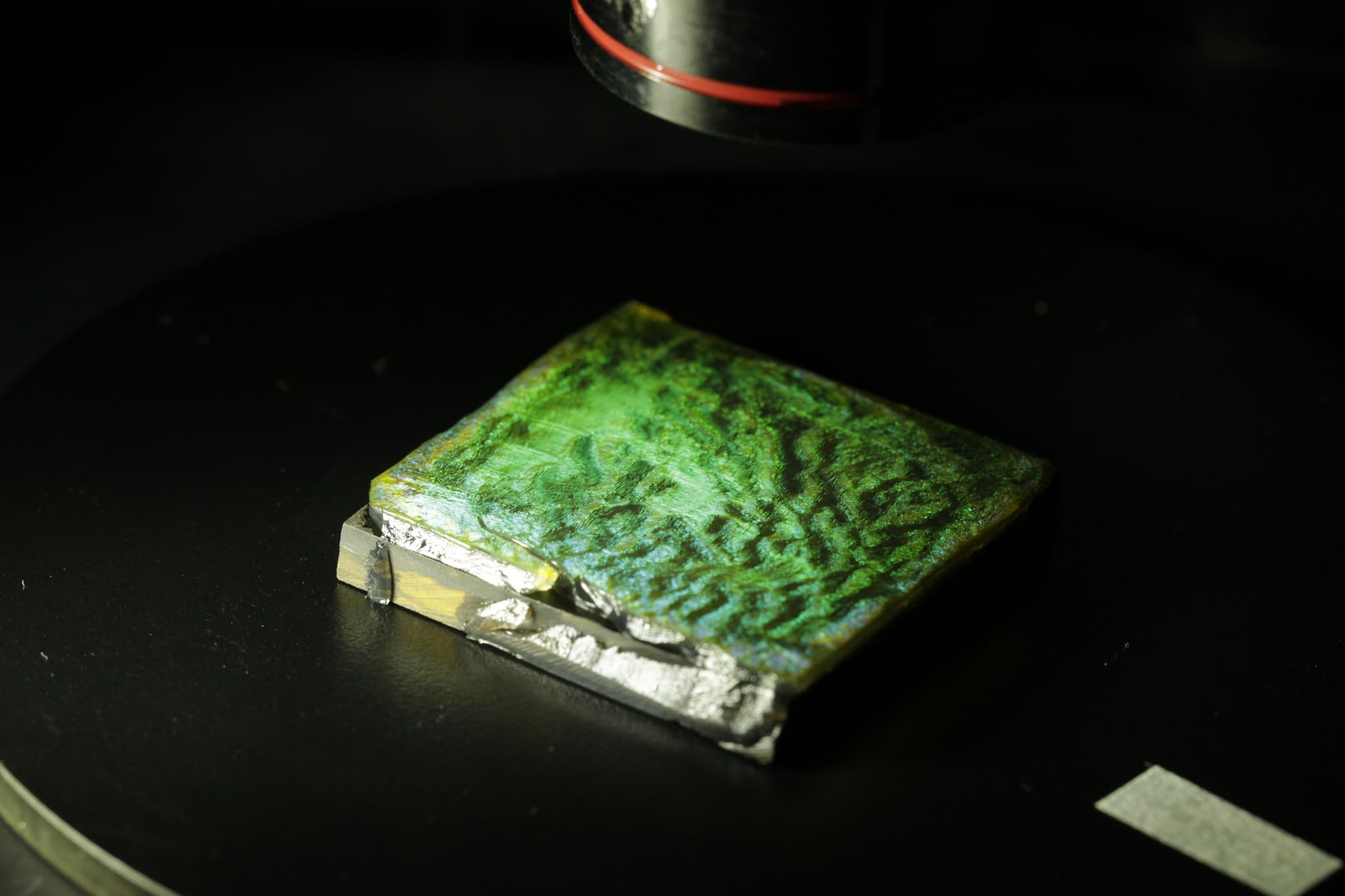

In other cases, my work begins with a scientific discovery. I frequently collaborate with biologists and researchers, translating laboratory findings into tangible objects or applications that drive sustainable innovation. A current project focuses on structural color derived from bacteria, exploring ways to scale it beyond petri dishes and apply it to design. This approach could offer a groundbreaking, eco-friendly alternative to the harmful pigments still widely used today.

In your work, you emphasize the integration of nature and technology, what are the biggest challenges in achieving this balance?

Exactly. I believe that new technological developments can actually bring us closer to nature rather than distancing us from it. Advances in technology allow us to accurately mimic nature, for example, by 3D printing structures found in the natural world that would otherwise be impossible to replicate. However, translating these structures into functional product designs is always challenging. Not all 3D printing technologies are the same, so I need to carefully consider which technology and material are most suitable for a specific application.

Additionally, 3D printing comes with its own limitations, meaning designs must be adapted to fit the constraints of the manufacturing process. These include factors like resolution and the fact that not all natural structures are printable with every technology. It’s a continuous process of exploration, figuring out how to translate these structures while maintaining their intended function within the design. This requires experimentation, and it rarely works perfectly on the first try. For me, it's also an intuitive process, balancing technical precision with a deep understanding of natural forms.

How do you see biomimicry shaping industries beyond design, such as construction, fashion, or even healthcare?

Biomimicry has the potential to revolutionize industries far beyond design by introducing more sustainable, efficient, and high-performing solutions inspired by nature.

In construction and architecture, there are already numerous nature-inspired innovations. For example, buildings influenced by termite mounds can regulate temperature without artificial heating or cooling, a principle already applied in passive cooling systems. In the future, I believe we'll also develop self-healing materials inspired by biological processes such as bone regeneration, resulting in longer-lasting, low-maintenance buildings and infrastructure.

In fashion, the structural color project I'm currently working on could offer significant value by replacing toxic dyes and pigments with sustainable, light-reflecting surfaces. Additionally, fabric production could be transformed through the study of spider silk, known for its remarkable strength and flexibility, leading to biodegradable, high-performance textiles.

In healthcare, biomimicry already plays a crucial role. For example, antimicrobial surfaces modeled after shark skin can reduce bacterial growth without chemicals. However, I anticipate regenerative techniques will soon become integrated as well. Researchers are investigating regenerative medicine inspired by organisms like salamanders, which can regrow limbs, potentially leading to breakthroughs in human tissue regeneration.

Ultimately, biomimicry encourages us to shift from extractive, wasteful production methods to regenerative, circular systems. By applying nature’s strategies, we can create smarter, more sustainable solutions across industries while deepening our connection to the natural world.

In your biomimetic designs, you replicate multi-functional natural structures using a single material. How do you computationally model and optimize the gradient transitions of material densities to achieve variable mechanical properties in 3D-printed objects?

The computational modeling and optimization of gradient transitions in material densities require a deep understanding of natural structures, hands-on experimentation, and an iterative design process. I start by studying multifunctional biological structures, such as cellular formations in plants or trabecular bone, where material distribution naturally balances strength, flexibility, and weight efficiency.

Unlike fully computational approaches, my process begins manually by modeling and 3D-printing small experimental structures. I then physically test these models under various forces, such as pressure, to observe their responses. This hands-on experimentation allows me to refine and combine different structures and properties into a cohesive design. Rather than relying solely on generative design algorithms, I often depend on intuition and direct manipulation, which provides greater control over both the functional and aesthetic aspects of the object.

While I occasionally use topology optimization to analyze material distribution for strength, I find that computational predictions for 3D-printed structures can be challenging. The final mechanical properties are heavily influenced by material choice and printing technology, whether it’s sintering, binder jetting, or FDM. Because of this, my design process often follows a trial-and-error approach, much like nature itself, where adaptation and refinement lead to the most effective solutions.

In soft seating and bicycle saddles, you've used 3D printing to achieve differential mechanical responses within a single material. Can you elaborate on how you employ topology optimization and generative design algorithms to achieve these functionally graded structures?

In my work with soft seating and bicycle saddles, I aim to create functionally graded structures from a single material, inspired by natural efficiency. While topology optimization and generative design can be useful tools, I primarily adopt a hands-on, intuitive approach to designing these structures.

I start by manually modeling and 3D-printing small experimental structures, then testing how they respond to external forces such as pressure and load distribution. Through trial and error, I refine these designs, combining different structural elements to achieve the ideal balance of flexibility, support, and durability.

Generative design can help structure complex forms, but it often reduces control over aesthetics and function. Instead, I prefer a more direct design approach, ensuring that structures not only perform optimally but also align with my vision for aesthetics and biomimetic design. This iterative process mirrors nature’s method of refining structures through adaptation and evolution.

Looking ahead, do you anticipate advancements in nanoscale additive manufacturing or biofabrication techniques (such as bacterial or fungal-based bioprinting) to enable self-assembling or self-replicating biomimetic materials that further blur the line between nature and design?

Absolutely! I believe advancements in nanoscale additive manufacturing and biofabrication techniques will play a crucial role in pushing the boundaries between nature and design even further. Technologies such as bacterial- and fungal-based bioprinting hold incredible potential for creating self-assembling and self-replicating materials, which could lead to entirely new ways of designing and manufacturing sustainable products.

Nature already provides us with countless examples of self-organizing structures, from mycelium networks that grow into functional materials to bacteria that produce structural color without the need for harmful pigments. If we can harness these biological processes and integrate them into digital fabrication methods, we might create materials that not only mimic nature but also actively respond to their environment, repair themselves, or even evolve over time.

The biggest challenge lies in scaling these processes while maintaining control over material properties and structural integrity. However, as computational design, synthetic biology, and advanced manufacturing techniques continue to merge, I foresee a future where the gap between biology and technology disappears, leading to a new paradigm of regenerative, truly circular design.