Global waste data shows how easily sustainability claims fall apart. The world generated 353 million tonnes of plastic waste in 2019, but only 9% was recycled, while ~50% was landfilled and 22% leaked or burned in the open.

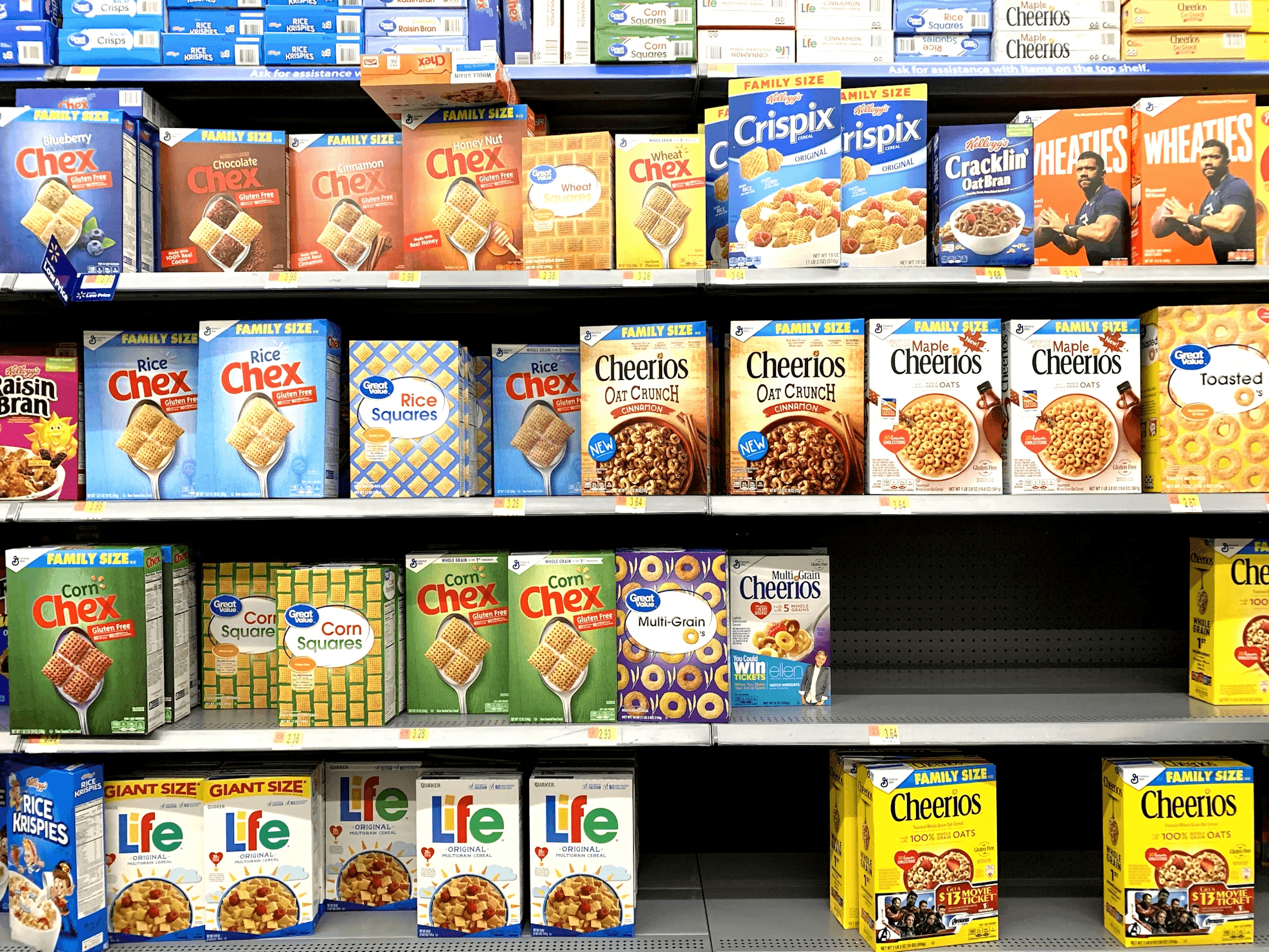

Packaging makes up ~40% of this flow, yet recycled plastics may reach only ~12% of total plastics use by 2060. With bioplastics at just 0.5% of global production and plastics trade exceeding $1 trillion, most claims still drift far from the system they operate in.

1. LCAs that stop before the bin

Most packaging LCAs still rely on optimistic end-of-life assumptions that do not align with global realities. In 2019, the world generated 353 million tonnes of plastic waste, yet only 9% was recycled. The remainder was incinerated (19%), landfilled (~50%), or leaked into the environment or open burning (22%). These flows matter: any LCA that assumes “closed-loop” outcomes without reflecting these baseline probabilities significantly inflates sustainability performance.

How end-of-life modelling inflates circularity

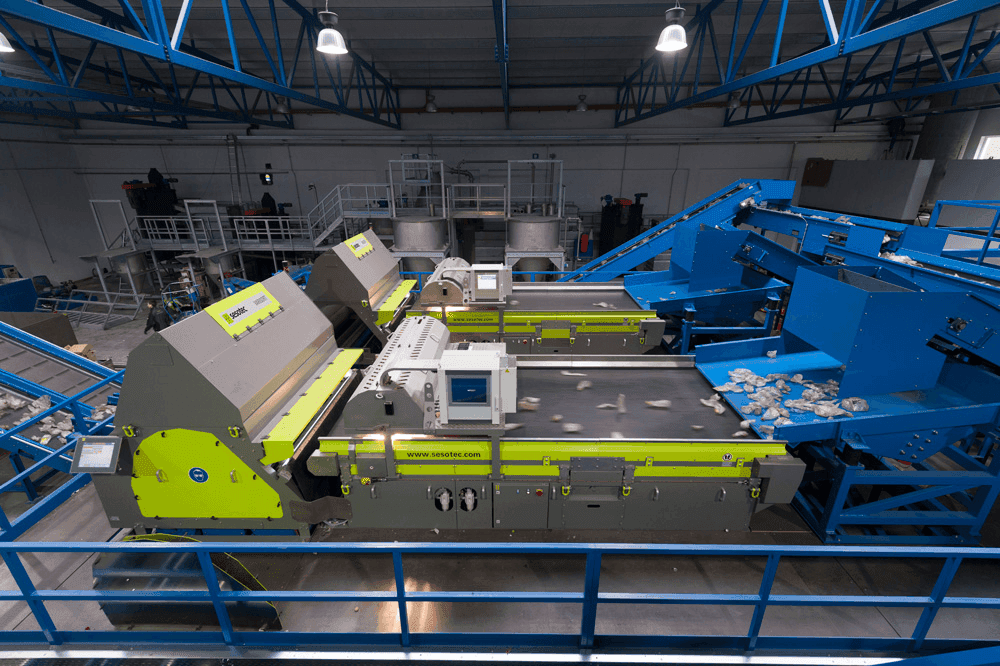

OECD data is explicit: 15% of plastic waste is “collected for recycling,” but roughly 40% of that stream is lost as residues during sorting and processing. Treating “collected” material as “recycled” overlooks this attrition and masks the waste and leakage implications that dominate real-world plastic flows. LCAs must therefore model the fate of materials based on data, not aspiration.

2. Certificates in a trillion-dollar, multi-step chain

The global plastics economy exceeds USD 1 trillion per year, accounting for about 5% of all world merchandise trade. That scale spans primary polymers, intermediates, finished goods and waste, moving across multiple borders and intermediate processors. In a chain this fragmented, documentation failure is systemic: certificates get out of date, scopes don’t match processing sites, and chain-of-custody claims are frequently misapplied.

Where certificate integrity typically breaks

International agencies highlight the need for traceability precisely because of this multi-stage complexity. To limit misuse, many schemes maintain public certificate databases, where scope, expiry and site alignment can be verified. When documentation doesn’t match the real substrate, converting step or supplier location, the sustainability claim collapses-not because of intent, but because of structural weaknesses in global plastics trade.

3. “Recyclable” versus what actually happens

Packaging is responsible for around 40% of global plastic waste-the single largest contributor to the waste stream. Yet despite widespread “recyclable” logos, global recycling outcomes remain stagnant: only 9% of all plastic waste is actually recycled. The remaining 91% is incinerated, landfilled, exported or leaked. A material may be technically recyclable, but without functioning local systems, it will statistically end up in disposal or the environment.

Why technical recyclability diverges from real outcomes

Infrastructure determines fate. Even when a material is labelled recyclable, many regions lack the collection or sorting systems needed to capture it. OECD’s Global Plastics Outlook and Our World in Data’s plastic waste analysis show persistent leakage, high contamination rates and limited processing capacity, factors that reduce recyclability from a theoretical attribute to a low‑probability outcome. As long as recycling systems remain uneven, packaging formats cannot rely on technical recyclability to demonstrate sustainability performance.

4. “Bio-based” that is tiny and opaque

Globally, bioplastics production capacity is about 2.47 million tonnes (2024) versus ~414 million tonnes of total plastics-just 0.5% of annual output. Even if capacity grows to 5.73 million tonnes by 2029, bioplastics remain marginal relative to petrochemical streams. In such a small category, traceability determines whether bio-based claims signal genuine material transition or simply a cosmetic adjustment.

Why origin and land-use evidence define material credibility

Because bioplastics represent such a small fraction of global production, their climate and land-use impacts hinge on feedstock source. Without documentation of origin country, crop or residue type, traceability or mass-balance schemes, and land-use considerations, bio-based content can easily mask conversions of agricultural land, competition with food crops, or supply instability. Brands risk overstating the systemic significance of bio-based inputs if traceability is not present.

5. Single-issue claims that blur system-level trade-offs

Packaging has driven ~40% of global plastic waste generated over the past two decades and accounts for close to 40% of virgin plastic resin demand. Given this concentration, system-level performance cannot be captured through a single metric such as CO₂. OECD projections show that even under strengthened policy scenarios, recycled plastics may reach only ~12% of total plastics use by 2060-up from 6% in 2019-indicating that waste and leakage pressures will remain dominant.

How single-metric framing obscures real risks

Climate-only narratives overlook water demand, resource depletion, end-of-life leakage and product-loss effects-all critical drivers of packaging’s environmental footprint. With recycling plateauing and leakage entrenched, any sustainability argument built on one metric cannot reflect the broader system dynamics shaping material risk, resource pressure and regulatory exposure.

These five red flags highlight where packaging sustainability claims most often collapse-when LCAs ignore end-of-life, certificates don’t match real supply chains, recyclability fails in practice, bio-based inputs lack traceability, or carbon metrics mask deeper trade-offs.

See what credible, system-aligned packaging looks like in the Tocco Report: REUSABLE PACKAGING 2030 Special Edition