Across the EU, only 48% of municipal waste is recycled or composted, and organic waste infrastructure is even more constrained - just 17% of municipal solid waste is composted or anaerobically digested, supported by roughly 5,800 bio-waste treatment sites for 450+ million people.

Meanwhile, bio-based plastics represent ~0.5% of global plastics capacity, making plant-based claims closer to branding than system change. Under PPWR, ESPR and tightening green claims rules, gaps between “green” story and real infrastructure are turning from marketing risk into compliance liability.

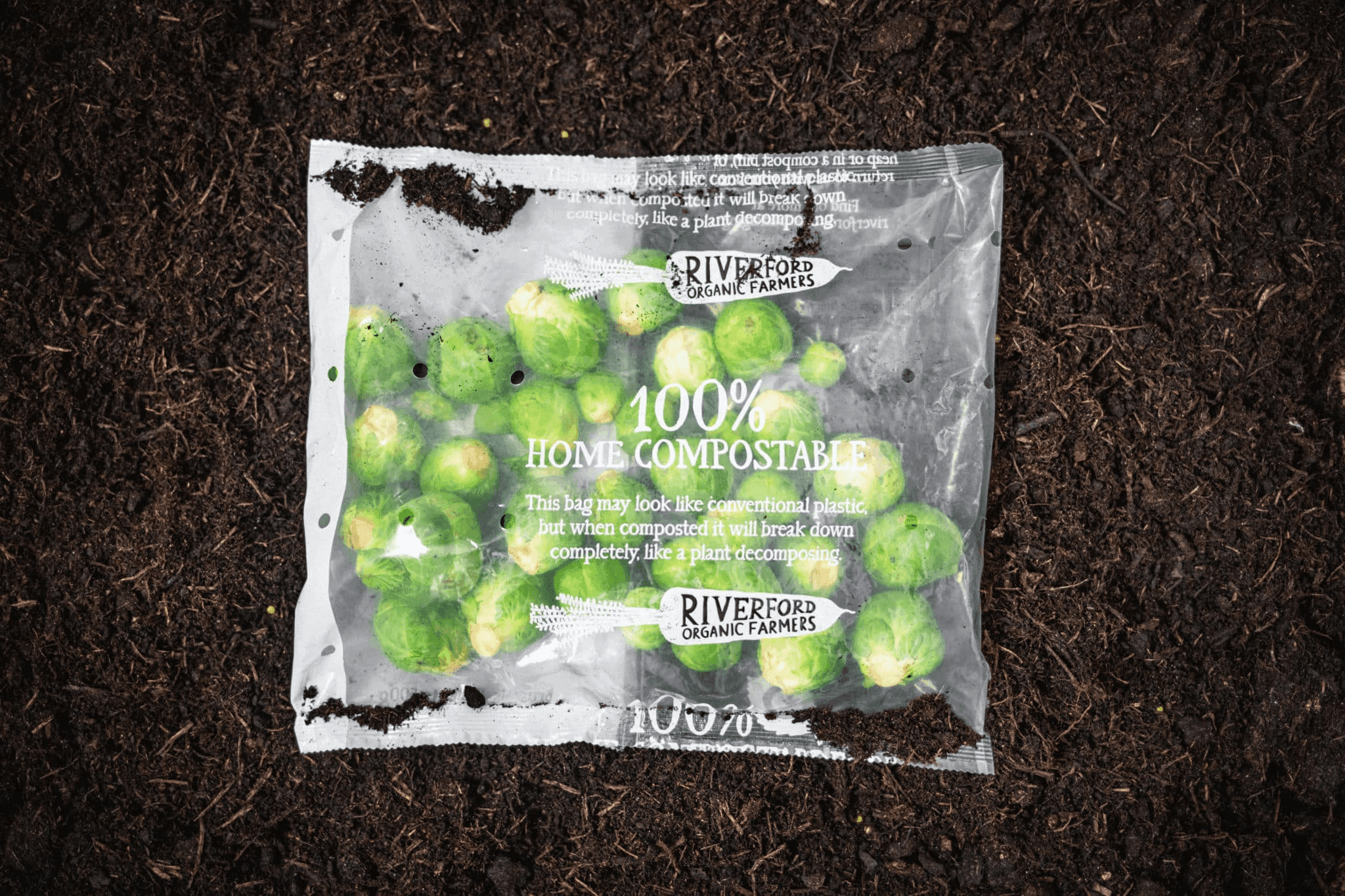

1. Compostable plastics in “zero-infrastructure” markets

Dropping PLA or compostable wrappers into regions without composting isn’t circular - it’s a regulatory red flag. In many markets, organic waste is still landfilled or incinerated, meaning “compostable” packs generate methane or become contamination rather than nutrient.

Compostability is only valid where facilities exist

In the United States, the FTC Green Guides (260.7) require that ~60% of consumers must have access to composting facilities to justify an unqualified compostable claim. Yet only 31% of full-scale composting facilities accept bioplastic-coated paper, and 60% of “home-compostable” plastics failed to disintegrate after six months in the UK Big Compost Experiment. In these markets, “compostable” turns into deceptive-marketing exposure, not a circular solution.

2. “Bio-based” films using mass-balance accounting

Marketing language suggests a move away from fossil feedstocks, but mass-balance allows suppliers to blend minimal bio-feedstock with conventional naphtha and allocate “credits” downstream - meaning the film buyers receive may contain 0% physically detectable bio-content. Because carbon-14 testing exposes this instantly, the gap between claim and chemistry becomes an evidentiary risk.

Mass balance can claim bio origins without bio molecules

Under tightening EU green-claims rules - including the Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition Directive - brands must substantiate “bio-based” claims with traceable physical feedstock, not accounting models. Without segregated supply chains that trace molecules back to plant sources, “100% bio-based” printed on packaging may become non-compliant, especially once DPPs require feedstock origin fields that make mass-balance less defensible.

3. “Ocean-bound” plastic (OBP)

Ocean-bound plastic is not a regulated term, and typically refers not to ocean retrieval but to waste located within 50km of a coastline - which is functionally “municipal waste with a coastal postcode.” The marketing leap from coastal waste to “ocean cleanup” is where compliance risk accumulates.

Ocean imagery without ocean recovery crosses the greenwashing line

Since only ~0.5% of global plastic waste represents mismanaged ocean leakage, most OBP represents waste unlikely to reach the sea. Litigation has already targeted brands implying ocean retrieval when supply comes from land-based systems. Under emerging anti-greenwashing enforcement, if imagery suggests recovery from water but sourcing occurs from inland landfills, consumer protection law becomes the failure point - not sustainability performance.

4. Aqueous-coated “plastic-free” paper cups

Water-based coatings replace PE linings but do not eliminate polymers - and standard pulp mills cannot process these cups without specialized equipment. Even small coating percentages disrupt pulping, gumming machinery and diverting material to landfill.

Plastic-free claims collapse under single-use plastics rules

Linings make up up to 10% of cup weight, and the EU SUPD treats any polymer-lined paper cup - including aqueous - as single-use plastic requiring the “PRODUCT CONTAINS PLASTIC” marking. Brands promoting these cups as “plastic-free” risk claim-level non-compliance and consumer-perception backlash once mandated markings contradict marketing language directly on the product.

5. PVA “dissolvable” pods

Laundry and dishwasher pods wrapped in PVA appear to “disappear,” but dissolution is not biodegradation. Conventional wastewater systems lack the microbes and retention time needed to break PVA down beyond diluted micro-scale.

Soluble ≠ gone under microplastics scrutiny

Studies estimate ~75-77% of PVA passes through treatment intact. If soluble synthetic polymers become classified as microplastics under EU REACH updates, PVA pods face instant compliance reclassification - turning dissolvable marketing into liability when audited against end-of-life performance, not consumer perception.

6. Bamboo-melamine “natural” composites

Marketed as “plant-based” or “eco-bamboo,” these products rely on melamine-formaldehyde resin to bind the fibers - a petrochemical plastic presented as a natural material. The environmental story collapses the moment compliance frameworks request substance disclosure.

Banned in the EU and not recyclable or compostable

Germany’s BfR found migration levels up to 30× the safe limit when hot liquids contact bamboo-plastic composites. Since 2021 the EU has banned bamboo-plastic food-contact materials entirely. They fail recyclability, misrepresent composition, and trigger recall exposure - a trifecta of compliance traps hidden behind a natural aesthetic.

7. Oxo-degradable additives marketed as “biodegradable”

These additives fragment PET or HDPE into microscopic particles rather than mineralizing to soil - creating invisible pollution under the banner of biodegradation.

Explicitly banned as microplastic generators

The EU SUPD explicitly prohibits oxo-degradable plastics, and the US FTC has prosecuted misleading “landfill-biodegradable” claims where full decomposition within one year cannot be demonstrated - an impossibility in anaerobic, low-temperature landfill conditions. Additive-driven fragmentation is now a legal dead end, not a sustainability strategy.

8. The refillable hygiene trap (BYO containers)

Refilling stations reduce packaging volume but shift hygiene responsibility from retailer to consumer - creating exposure where food safety systems and carbon modelling intersect.

Reuse without HACCP-aligned sanitization becomes a compliance gap

Under PPWR, reuse targets (e.g., 10% of beverages by 2030) require demonstrable systems, not goodwill. To remain HACCP-compliant, retailers may need high-temperature or chemical sanitization - increasing water and energy footprints in ways that undermine claimed environmental benefits and introduce liability should contamination occur. Refill, in this context, becomes a system design question, not a signage initiative.

Q&A Session

Why do many “green” packaging ideas become compliance risks?

Answer: Because ESPR, PPWR and DPP require proof of recyclability, infrastructure readiness and material traceability. Formats that rely on claims rather than evidence fail once audited against real system data.

When are compostables and bio-based claims non-compliant?

Answer: Whenever local infrastructure cannot process them, or when claims imply physical bio-content that mass-balance models cannot prove. Both fall under EU green-claims enforcement and DPP-origin traceability.

Which “eco” materials are most at risk of immediate regulatory failure?

Answer: Bamboo-melamine composites, oxo-degradables, mislabelled “plastic-free” cups, and dissolvable PVA pods. Each conflicts directly with EU bans, SUPD rules, or emerging microplastics and feedstock-disclosure requirements.

Conclusion

The next phase of sustainable packaging won’t be won by logos, leaves or labels - but by proof, performance and product data that stands up in audit rooms, not brainstorms.

See how leading brands are redesigning for that reality in the Tocco Report: Tocco Report: REUSABLE PACKAGING 2030 Special Edition.