Your installations and sculptures often use biodegradable materials. Can you discuss the process and challenges of working with these materials?

Until 2017, my work did not fully account for the extent of contamination involved in its materiality. Although I was aware of environmental contamination issues, I mistakenly believed that art was exempt from such responsibilities. Gradually, I began to actively educate myself on this topic and sought out non-polluting materials for my work.

Today, I focus on compostability, not biodegradability, as it is a clearer and more measurable concept. I aim for 100% domestic (not industrial) compostability as a starting point.

The challenges are significant. First, we must see ourselves as individual agents of change, beginning with education and responsible research. Next, it is crucial to communicate the importance of adapting to drastic environmental changes and to understand our roles as artists and designers in responding to these changes.

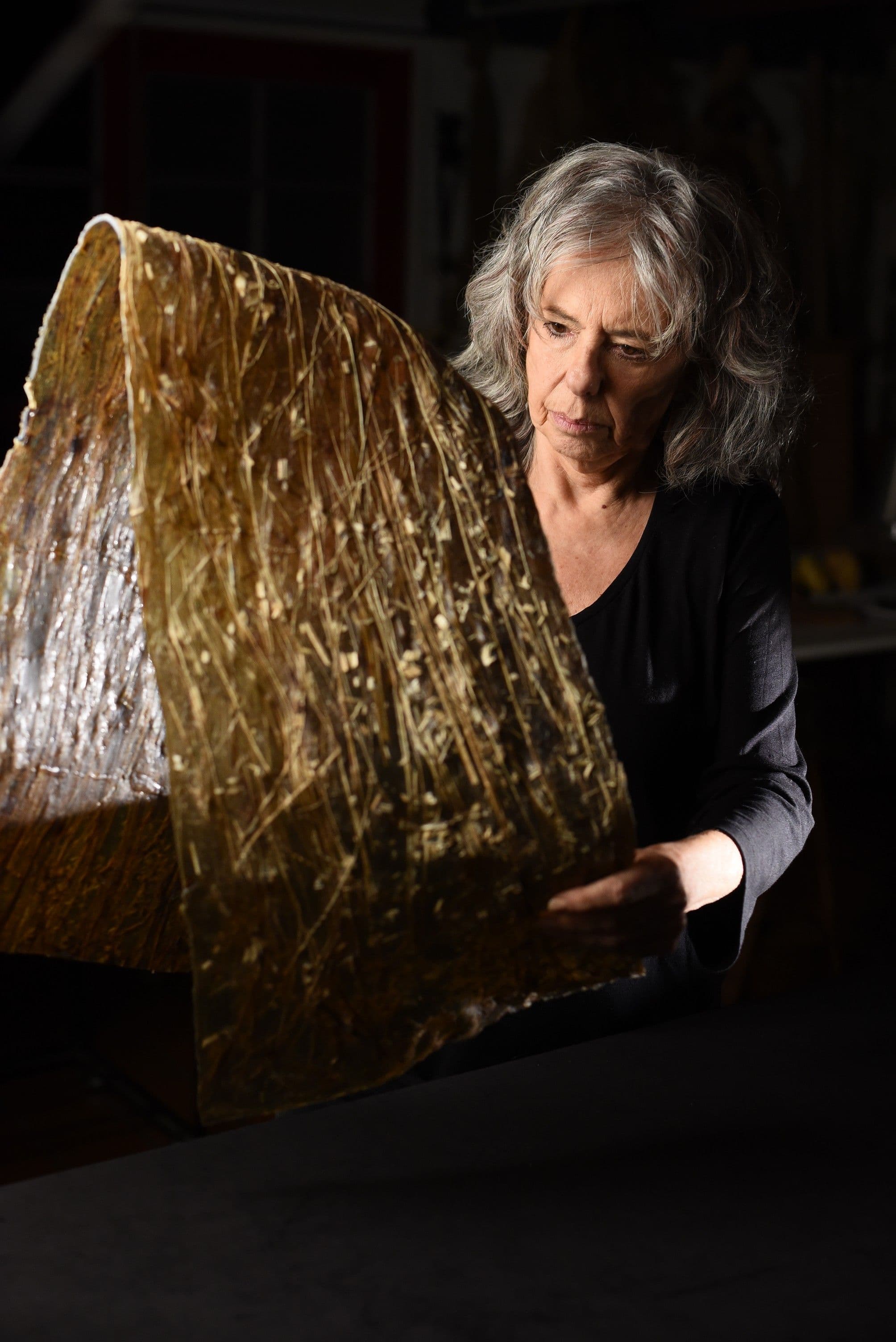

Your bioleather project, Moebio, uses plant and bacterial cellulose from kombucha. Can you detail the scientific process behind creating bioleather from kombucha cultures and the specific challenges you encountered?

The process for Moebio bioleathers, as for any biomaterial I intend to produce, consists of starting with a simple formulation and applying the method of iterations — that is, 5 to 10 tests modifying one parameter at a time in appropriate proportions. The best results are then subjected to resistance tests under different demands.

From these values, the necessary steps are modified again to reach the appropriate result for a specific need.

Can you explain the techniques you use to integrate biomaterials into your sculptures, and how you ensure these materials maintain their structural integrity over time?

I don’t expect biomaterials to last as long as plastic since the duration of plastics is a problem in itself. We should reconsider the assumption that what lasts is good and what doesn’t last is not, and instead consider the entire life cycle of a material.

For example, plastic can be useful for a few hours and then remain for thousands of years as garbage and pollution. Animal leather can last for many years but with an excessive amount of contamination in its initial tanning. Biomaterials, in different versions, are produced to last perhaps 5 years, perhaps 100, but after that time, they will become fertile land. So, we could talk about an eternal duration at the service of nature. It is the points of view that we should rethink, perhaps.

In what ways do you think the art community can contribute to the discourse on climate change and environmental justice?

The artistic community always contributes to metabolising and reacting to the reality in which it lives. At this moment, beyond the way each artist proposes, what I suggest in my talks is to take charge.

What do I mean by this? Symbolic language falls short in the face of the urgency of the disaster. The image of the orchestra playing on the deck of the Titanic is well known. I propose to help assemble the lifeboats.

When collaborating with scientists and tech companies on sustainable materials, what key technical criteria do you consider to ensure the materials meet your artistic and environmental standards?

There are no technical criteria or standards anymore for art to remain art. If it reaches people, it is art; if not, it is not. Regarding the environment, we propose many things. To summarise: first, not harm. Then, understand what is harmful and why. Third, take the simplest, cleanest solution with the lowest possible energy expenditure and carbon emissions.

As the founder of Escuela de Proyectos and organiser of the Platt Award for the Arts, what advice would you give to emerging artists focused on environmental and sustainable themes?

They should be informed and move away from individualism because today, the personal name is no longer what matters.

Art must be linked to science; otherwise, it is not sufficient. They should group, form collectives, and make concrete proposals and actions. They should also consider that if their works contaminate or the waste from their works contaminates, if the inputs are contaminating, that contamination invalidates the meaning.