The Lockwerk collection features prominently in your recent work. What drew you to stainless steel as the primary material, and what challenges have you encountered in working with it?

The choice to work with stainless steel has been very spontaneous to me. I come from a family of carpenters and metalsmiths, and I started to have a relationship with this material when I was a kid.

At first, it was just the fascination for the workshop, that felt like a magic place where things were created from scratch, but also as some sort of playhouse. I remember driving through the warehouse on the forklift with my grandpa, sitting on his lap. Then when I was a teen strong enough to handle tools safely, I started working there during summer breaks from school, and then it became something I used to do now and then even during my college years. Then, when I first started working with other studios I had the chance to explore other materials, such as epoxy resin and solid wood, but I always felt that metal suited me the best.

So the choice of working with metal was in some way “natural” to me, also because it was easier to start my practice using the materials I knew the most, and of course, my family background came with some useful vantages: I did not need to buy machinery or tools to start, I had an established supply chain for materials and local artisans related to metalworking that I already knew and whom I could easily relate to.

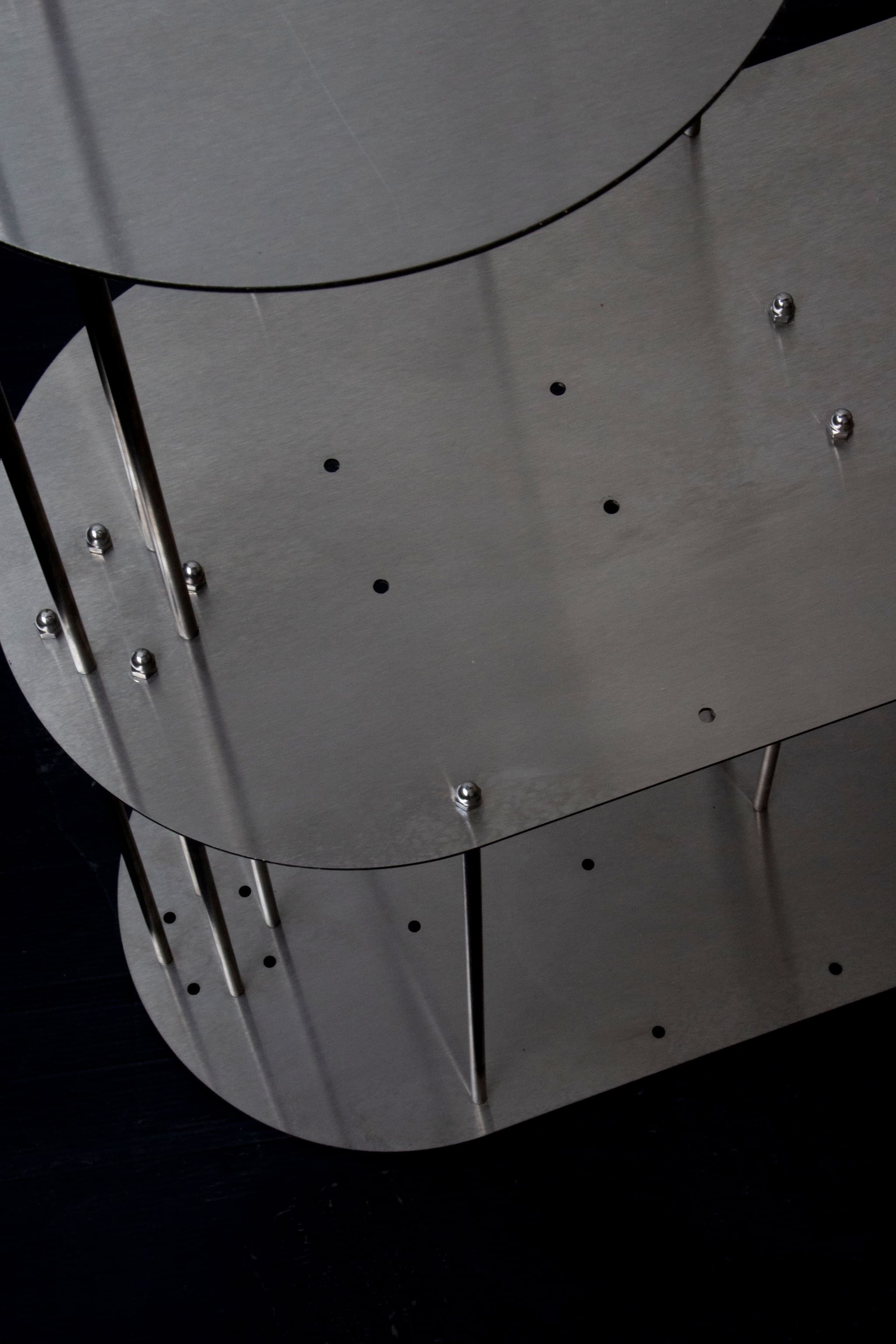

I decided to work with stainless steel for its aesthetic and physical properties: in between metals, stainless steel is the most resistant, doesn not need to be painted or treated to avoid rust or oxidation, and has, in my opinion, the best surface texture when hard brushed, that is the finishing I use and that can be very helpful to minimise small imperfections, which is very important in metal working.

In some ways, working with steel was for me a choice to avoid problems and minimise issues shortening the process. At the same time, you have to deal with the cost of a material that is not cheap, especially when using some high-quality kind of steel sheets to avoid the material bending or getting easily damaged. Using a “raw” material, with no finishing, involves the necessity of being very careful and respectful in every step of the production process.

Can you discuss the significance of exposing fittings such as screws and bolts in your designs? How do you believe this transparency in design elements affects the user’s interaction with the furniture?

In the beginning, it was an aesthetic and “political” choice: while I was experimenting with a metal design for some years, waiting to be ready to launch my first collection, at some point steel and aluminium became all of a sudden a huge trend in contemporary design, especially in collectible. But something felt wrong to me with a lot of the products related to this trend. Most of the designers used metal as if it were any other material, without taking into serious consideration its peculiarities (and this is an issue for any material in contemporary design, actually). I couldn not find any intent to valorise metal in these huge and unnecessarily heavy objects that tried to decline metal texture and finish to some forms that didn’t exploit all its other physical properties. Hence, I tried to detach myself from the trend, not in a polemical way, but trying to approach things from a different point of view.

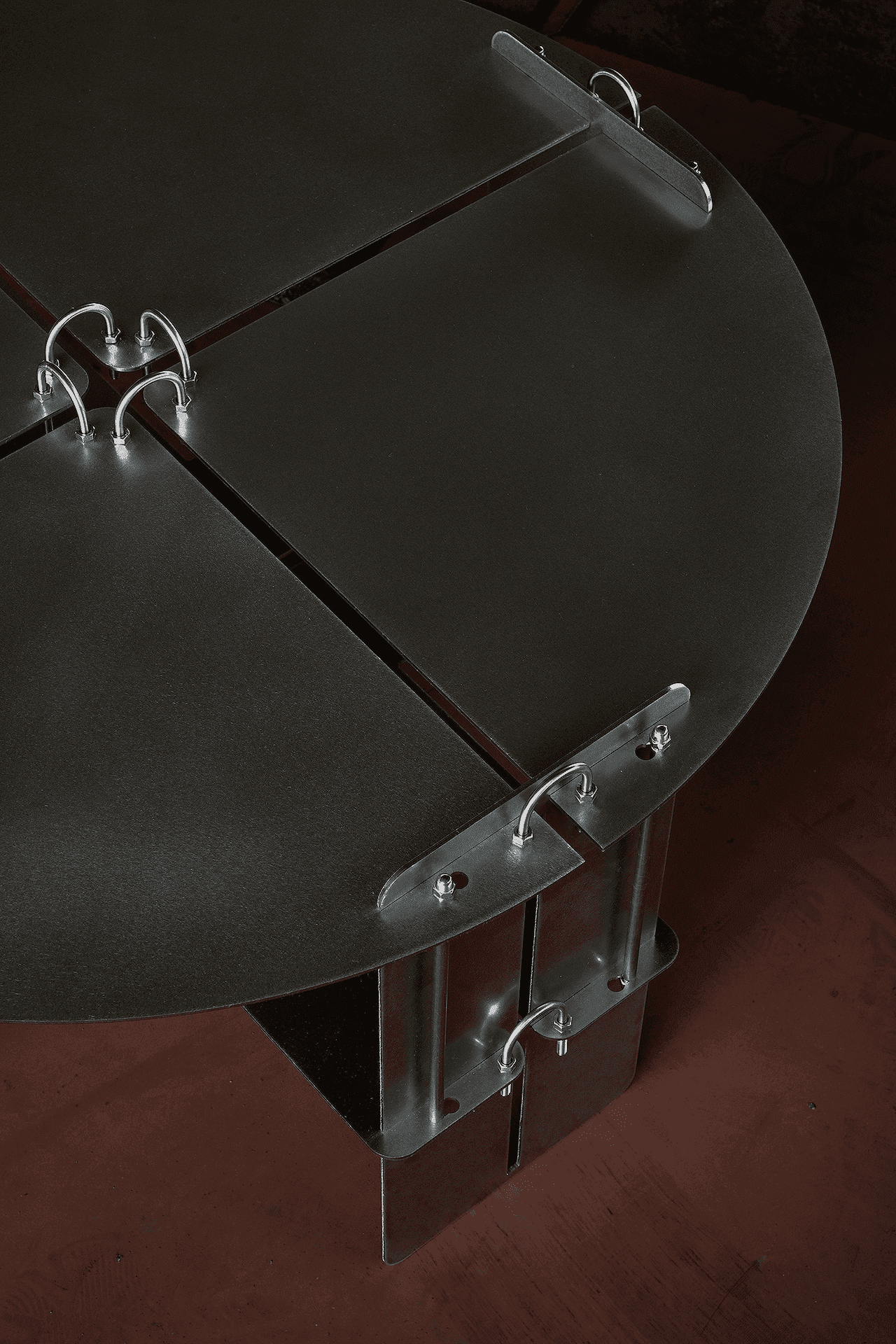

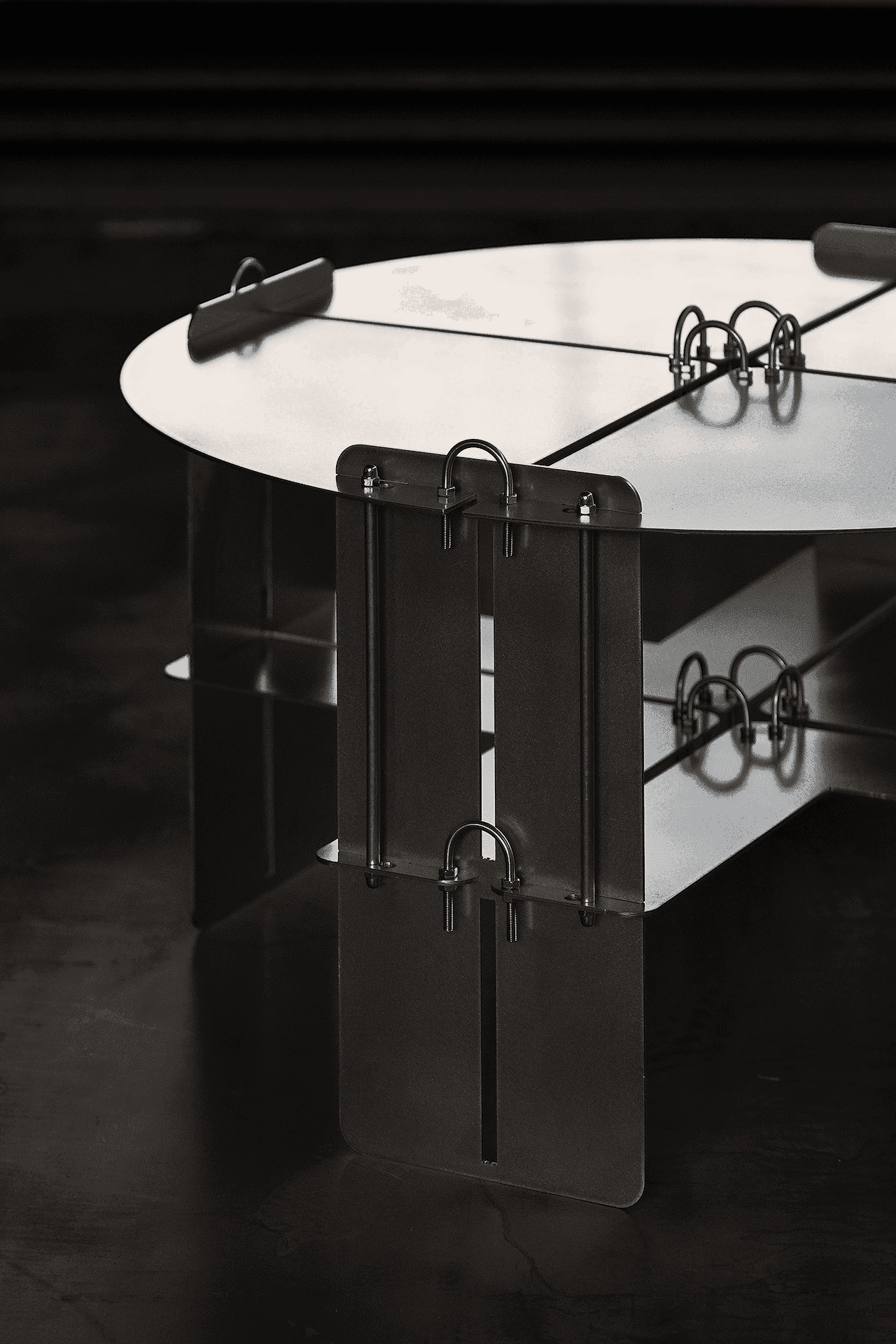

I tried to use a smaller amount of material, exploiting steel strength to develop a solid and “empty” structure, using only rods and metal sheets, cut and bent. Simple as that. Thereupon the issue of hiding connection elements, such as screws and bolts, came up. Traditionally these connecting elements are hidden as much as possible in furniture design, but it was impossible to hide it and at the same point stay loyal to the kind of formal research I was pursuing. So I decided to highlight them instead, making them a recognisable element of my language and style.

This is strictly connected to the topic of making my furniture completely self-assembled, to minimise shipping impact and costs. Highlighting connection elements makes it easy to assemble and understand. Also, I hope, it makes the core concept something that is immediately clear and recognisable, beyond any necessities of complex storytelling. It is right there, clear and simple, such as screwing a bolt. I think that when we can understand how something is done, it becomes easier to understand why it has been done that way, and from that to get to the very first spark that led to that concept. I think that ideas give a special value to an object only if you can perceive the idea through the object itself, not if you are taught how to look at it. It’s very difficult to achieve, and I think I am not there yet, but it is for sure something that I aim to do when I design.

Your work seems to embody a minimalist yet functional aesthetic. Could you describe your approach to achieving this balance and any influences or inspirations that guide your minimalist design philosophy?

I could name a lot of designers and artists that I consider greatly inspiring for my work, but I think that will be reductive of how things work for me. Indeed, I keep in great consideration the inspiration I get from design and art culture, but in the same way, I am inspired by a lot of other things, from the music I hear to the food I eat, the clothes I wear, the people I know, the streets I walk.

I think it is the same for everyone: our inspiration comes from a huge cloud of elements and experiences from every aspect of our life that contribute, each in its own unique way, to create an aesthetic that resonates with us.

Therefore I think it is more interesting to focus on the design process. I am not a huge fan of the “forms follow function” formula, but still, my idea of a well-designed object resides in the relationship between these two elements.

As I mentioned, the idea from which I started to design my objects was for them to use less material and to be self-assembled. These two “functions” (or pragmatical needs we can say) did not automatically transform into a form, but sure set some limits to the formal aspects.

I always thought that having a limited range of options is a key aspect to focus your creative process, so I always start to design setting some boundaries for myself: a particular form or aspect I want to explore, a function that the final product must perform, something like that. Then, it is important to understand when the process you started leads you to the limit of the boundaries you set: I think that the design that will satisfy me is to find somewhere on that edge.

The Lockwerk Coffee Table and Lounge Shelf have been recognised for their innovative design. Can you share the development process behind these pieces, from initial concept to final prototype?

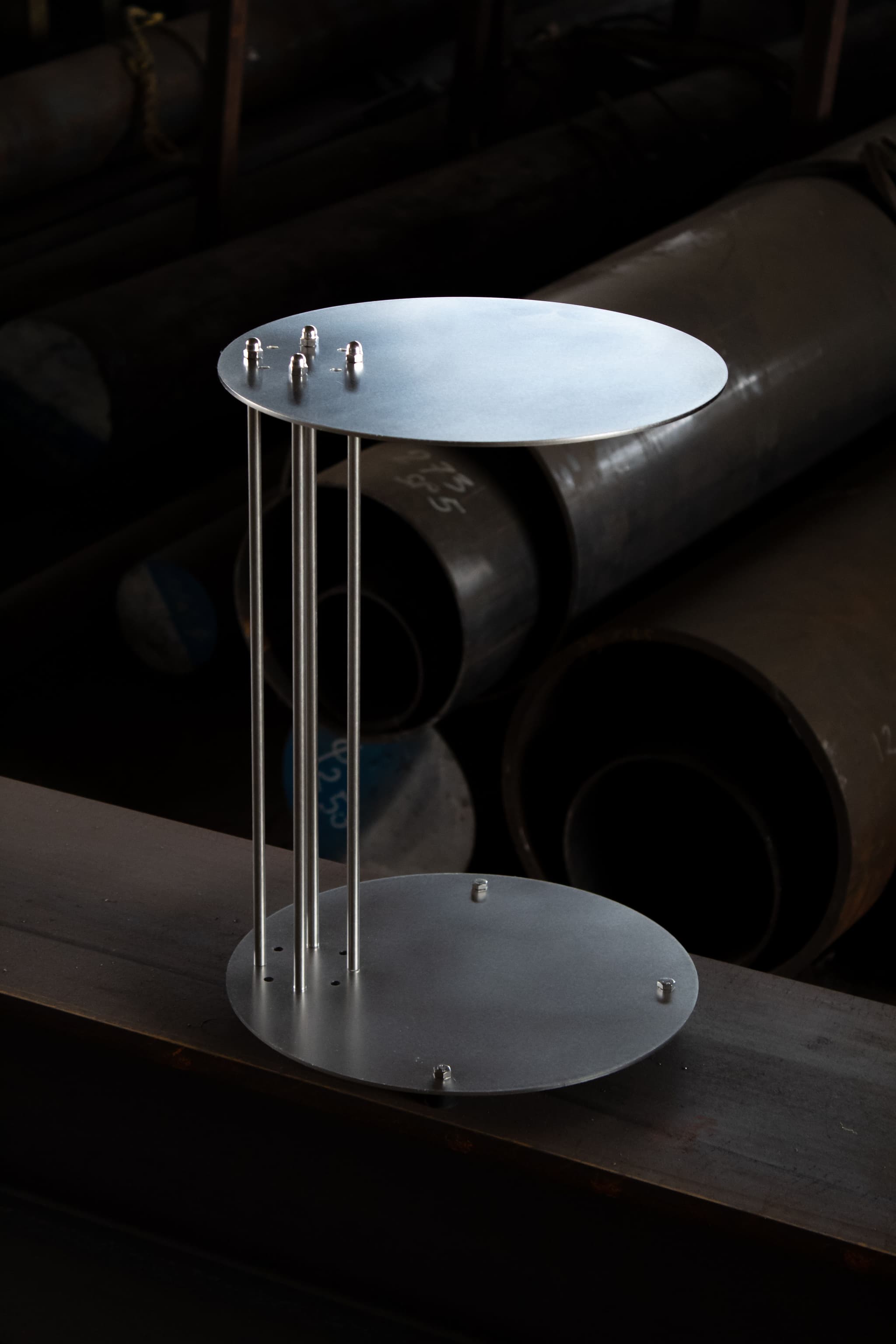

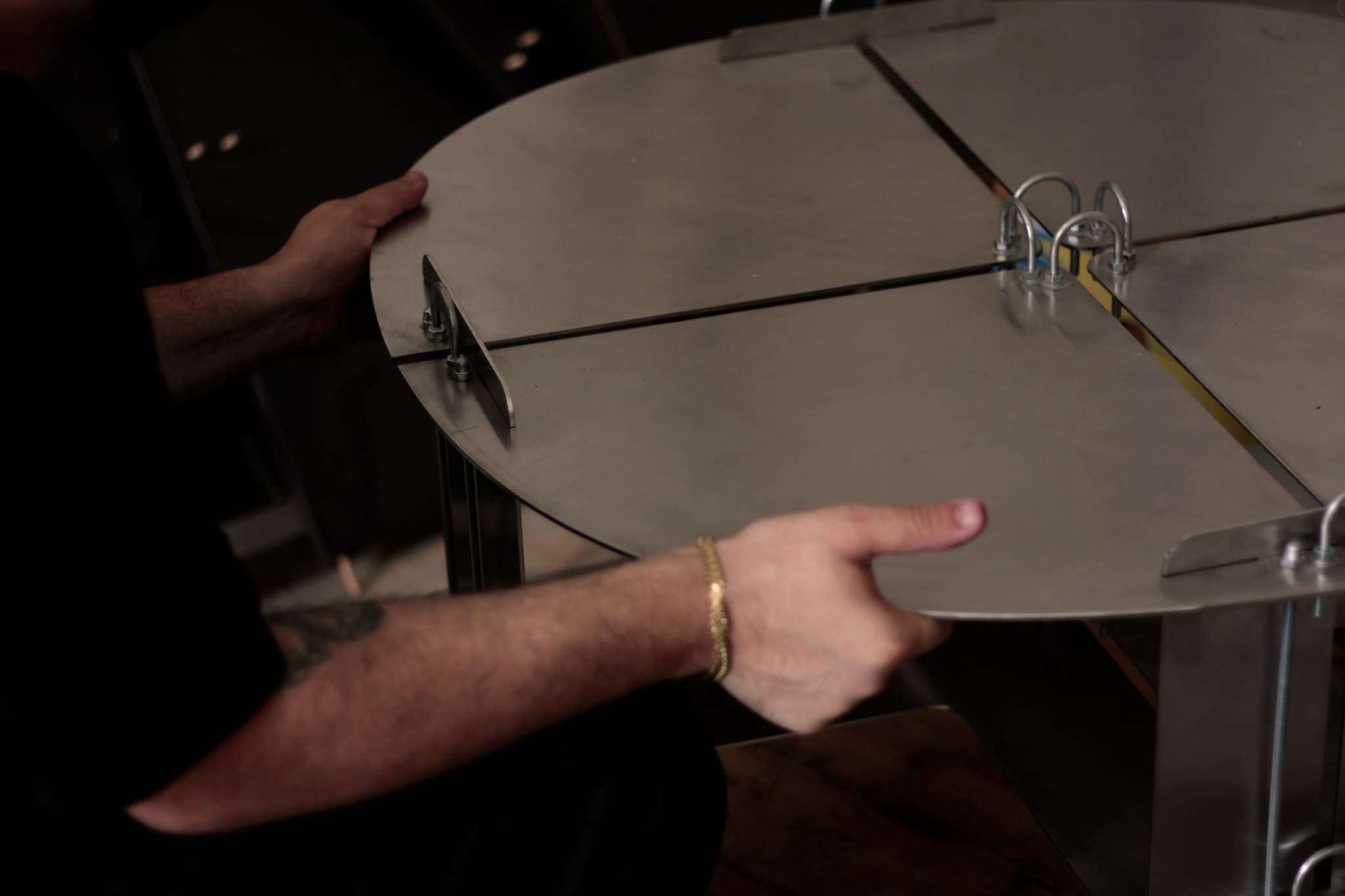

As I mentioned everything has started from the idea of creating some self-produced furniture pieces while keeping in consideration some industrial aspects such as self-assembly, reduced shipping volume, and reproducibility. It all started there. Also, I wanted to experiment with joinery. Lockwerk Coffee Table is the first piece of the collection, and it brings all these aspects to the maximum: it involves the use of rods, U-joints, and the intersection of the metal sheets themselves.

It is what is usually considered as a statement piece, some kind of manifesto object.

Lockwerk Lounge Shelf (as with every configuration of the shelving system) simplify this research in a simple object that embodies the topic of customizability, one of the aspects I wanted to focus on at that time.

Regarding the actual prototyping, the issue regarded the details: how to exploit at its best the strength of the steel rods, how to make it easier to assemble the pieces, and how thick the metal sheets needed to be as thin as possible and still not to bend.

Customisability is a key feature of your Lockwerk Lounge Shelf. How do you ensure that each customized piece meets both aesthetic and functional requirements? Are there specific tools or techniques you use to manage this customizability?

One of the aspects I kept in great consideration, regarding the shelving system, was allowing myself to design something that can be implemented with new elements, to become more and more functional. Right now, I am studying how to implement closed modules for storage and hanging racks for fashion retail purposes. I liked the idea of these objects being the starting point of a research and development process.

I’m open to the possibility that these new elements could come not only from my ideas but also from some customisation needs.

The objects itself it is not difficult to customise when it comes to configuration or size because it has been conceived for that purpose. But I think that what makes it special is the fact that it offers the possibility of rethinking it from both the designer's and the customer's perspective. It offers more than what is “on the menu”, you can ask for modification and we’ll understand together if it is possible to do it.

That is not an uncommon process in self-produced design of course, but I think that Lockwerk Shelf (being the technical, minimal radicalist object it is) offers a wide range of functional possibilities without losing its defining elements and personality.

Looking forward, what are your aspirations for your career in both design and curation? Are there particular projects or goals you are aiming to achieve in the next few years?

I will be extremely honest and tell you something is not so common to hear out because it breaks the glamorous aura surrounding the designer’s work, but everyone in the industry knows. My first goal is economic sustainability itself.

Every designer, especially the ones that self-produce their work, knows that it is very difficult to make a living out of your pieces. A lot of designers have a second job, or in many cases, we could say that their products are the second job. To me, it has been the same for almost four years, even if right now I decided to give myself a year to focus on my brand, after working for other people’s studios.

That is a huge privilege, and not everyone can do it, I’m pretty sure that we’re losing amazing “designers to be” in relation to the economic privilege that is required to start a self-production path. To me it was the possibility of having a family business that gave me the space and the tools to start making my stuff, for other people it could be the money needed to start to work with artisans producing their stuff or affording materials, a workshop, some tools to start, the time it is needed.

While getting there, I hope I will have the chance to continue developing other aspects of my work that I keep in high consideration: I would like to write another book about contemporary design (I’m already working on something) and I hope I can continue teaching as I do now. I think that teaching is the thing where I can let my passion for design flow in the purest way, sharing my passion with students who are still experiencing the design process most funnily and excitingly.

I hope that this will keep me remembering how and why I started to design.