Key Points

- Builds multi-layer garments directly on the jacquard loom, minimising cut-and-sew and embedding structure into the weave.

- Works exclusively with natural, biodegradable yarns; deadstock is blended via a gradient system to resolve colour/consistency issues at source.

- Integrates collars, pockets, and shaping in-weave; some edge finishing still requires post-weave sewing due to fray constraints.

- Comfort and integrity hinge on strong warps without synthetics, developed with craft-oriented mills (wool and indigo cotton).

- Scale depends on mills willing to run small batches and share chemistry/transparency; hands-on residency work complements AI sourcing.

Full interview with Kelly Konings

1. Your practice challenges the traditional separation between textile and garment. What properties of jacquard weaving enable the creation of fully-formed garments without cutting or sewing?

Within weaving, you can work with multiple layers by splitting the warp yarns into different sets. This allows you to build positive and negative space, for example, forming a tube directly on the loom.

By combining these layers with pattern-cutting constructions, it's possible to create entire garments solely through weaving.

2. When sourcing deadstock yarns from the Swedish textile industry, what are your main quality or compatibility considerations during the design phase?

I focus on local production possibilities to support short, transparent value chains. However, Sweden has limited locally produced yarns, especially beyond wool. That led me to explore deadstock and production waste yarns, often in collaboration with Swedish design companies still producing locally.

In jacquard weaving, the yarn must pass through the yarn feeder, meaning it must withstand tension, be relatively even, and avoid breakage. I exclusively use natural, biodegradable yarns.

3. How do you assess the environmental impact of your yarn selections, particularly when balancing local sourcing with fibre performance?

I consider the origins of the yarn and, if it's deadstock, why it wasn’t used. I design textiles to fit the fiber, striking a balance between the material’s properties and the woven structure.

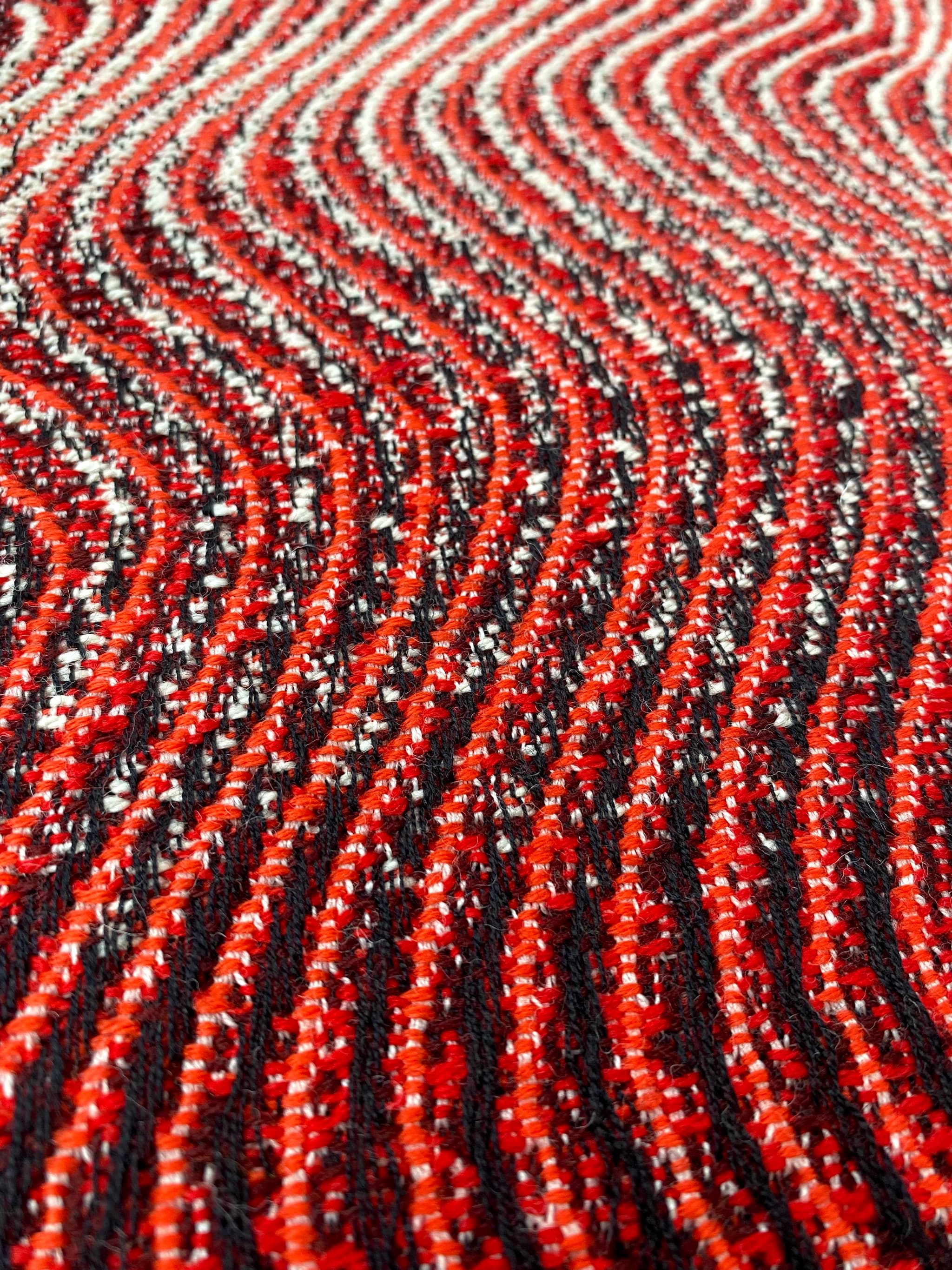

For instance, Swedish wool is coarse and better suited for lined or loosely structured garments. Many deadstock yarns exist due to colour discrepancies, outdated shades, or mismatched fashion trends. I developed a gradient system that blends various deadstock colours seamlessly, creating dip-dye-like shading effects.

4. Your “Hybrid Forms of Dressing” collection integrates elements like collars and pockets directly into the weave. What material constraints or breakthroughs made this construction possible?

One challenge is edge finishing, as woven fabrics tend to fray. Currently, jacquard looms can’t finish edges, so some post-weave sewing is still needed. Unlike knitwear, which allows for seamless finishing.

That said, I see value in pushing existing industrial tools like the jacquard loom toward future-fit applications.

5. Working with industrial weaving technologies, what material properties become critical for both structural integrity and wearer comfort?

Since I work exclusively with natural yarns, the warp must be strong without resorting to polyester blends. Partnerships with craft-focused weaving mills have been essential, whether in wool or indigo cotton warps.

Jacquard weaving lets me design both the aesthetic and structural aspects of a textile in tandem. The pattern is not an add-on but embedded in the fabric’s core.

6. In terms of scale, what are the biggest material or production hurdles you face when transitioning from prototype to small-batch production?

The hardest part is finding industrial weaving partners who are aligned with my values, interest in natural yarns, openness to experimental structures, and willingness to produce in smaller quantities.

I've successfully partnered with two mills that create custom textiles for their showrooms while also producing limited runs for my own collections.

7. With increasing pressure on transparency and traceability, what kind of sourcing or compliance information do you wish were easier to access from textile suppliers?

I’d love more clarity on the chemicals used during both yarn production, such as dye processes, and post-weaving treatments like chemical washes. Full disclosure would help designers make better-informed, lower-impact decisions.

8. Given your dual background in fashion and textile design, how do you approach the narrative potential of materials, not just in form, but in origin and production logic?

Fibres hold meaning, connected to place, people, memory, and cultural context. They carry technical reasons for their use, but also storytelling power. When a beautiful textile is used inappropriately, the result can be a poor-quality garment, not because either element is flawed, but because they’re mismatched.

My aim is to bridge this gap between fashion and textiles, aligning design logic across timelines and disciplines.

9. What opportunities do you see for AI-powered sourcing tools to support independent or experimental designers in locating high-performance, lower-impact materials?

AI tools are great, especially for independent designers navigating opaque supply chains. But nothing replaces visiting production hubs, touching, smelling, and hearing the machinery and materials in action. My residency at Lottozero in Prato, Italy, was transformative. It helped me trace the deadstock yarn journey and better understand how and why certain waste is generated.

10. Looking forward, what kinds of materials or supply chain shifts would enable greater experimentation within your weaving practice, especially for zero-waste construction?

I’m passionate about local textile labs where designers can experiment hands-on. The TC2 loom is a hand-operated digital jacquard. It lets me explore industrial-level weave structures by hand. I also use the HILO spinner, which lets me twist my own yarns.

More funding and support for these spaces would amplify what’s possible, expanding both access and experimentation.

→ The next decade of fashion is fibre-first. Download Fibers & Fabrics Future 2025-2026 for the new hand-feels, drapes, and surface languages shaping design now.