How would you define 'circular economy' within the context of built environment design?

The current discourse in the building industry mainly relates circular economy to circular building, which at the moment mainly revolves around re-use, upcycling, and refurbishment of buildings, interior products, and building materials. There is still a great lack of holistic insight into the circular economy.

The circular economy is based on three principles. To keep products and materials in use, design out waste and pollution, and restore natural systems. Only two out of the three are currently being addressed with the advent of the circular economy in the built environment.

Until recently, the focus has mostly been on creating a market around refurbishment, upcycling, and re-use of interior furnishing and materials. At the moment, there are well-established markets and collaboration networks that act on the frontier to make this kind of item accessible in public tendering, for instance.

There are also some established companies offering re-used bricks on a significant scale. The re-utilization of existing construction elements such as concrete and steel load-bearing systems is still a slow progression due to a lack of know-how, standards, cost-effective methods, and other incentives.

Product-as-a-service such as renting lighting, furnishing, or flooring is beginning to gain ground, but so far there is no clear pathway on how to scale up or how to count the carbon emissions when using circular business models.

In 2024, an ISO standard for the circular economy will be rolled out that will aim to unite the industries to form a common language and, in the long run, a framework for fair competition. Policies for counteracting design for obsolescence are still nowhere to be seen. Extended warranties are also relatively absent with the advent of circular buildings. It does raise difficulties in terms of shared warranty responsibility for building systems, as buildings can be seen as compounds or systems that interact rather than single products.

Recently, there has been an increased movement on how we go from sustainable building to sufficient building. In Europe, about 80-90% of the built environment demand is considered to be within the existing building stock. Instead of building new construction, we should make sure to use the existing building stock and transform it. This is often proven to be easier said than done. There is a great demand for building capacity to assess building re-useability and knowledge on how to transform buildings.

Another rising aspect is the way we use buildings. How can we create multi-tenant usage of buildings and increase the time they are being used? A third aspect that relates to both transformation and tenant planning is the design for flexibility. We must create buildings that can be used in many different ways and by a myriad of tenants.

To fully integrate the circular economy into the built environment, we need to look beyond the buildings. We need to create synergies and integrate cities, buildings, blue- and green structures, and food systems into an ecology of systems. We need to address the third principle of the circular economy to restore natural systems. Looking at the built environment, fifty percent of the urban cityscapes consist of hard surfaces such as roads, parking, sidewalks, etc.

When we plan the physical environment, we need to make assessments, making sure to head towards a circular economy and a regenerative society by restoring natural landscapes. When designing masterplans, we need to set requirements for low carbon emissions and healthy materials, as well as restoring nature.

For instance, when we transform an industrial area, we need to make sure nature is reintroduced in such a way that it supports a circular economy through integrated water management and food systems.

This gives us an important possibility for climate adaptation and mitigation while counteracting flooding and urban heat island effects, for instance. The cities need to act as platforms as well as regulate and incentivize actors to partake in and drive this transition. Promising projects are being led by the local governments in Munich, Amsterdam, and Tempere, for instance.

What are the emerging practices in built environment design that align with circular economy principles?

The perhaps most emerging topic is the one that 80-90% of the built environment is considered already built in Europe. This corresponds to retaining products at their highest value. This means we need to refuse to build new construction, avoid demolishing the built environment, and start transforming and using it.

We need to rethink flexibility and generality when we design. A design should be changeable over time so that it can adapt to future, unknown needs. About 75% of the European building stock is energy inefficient. In a circular economy, we need to circulate resources such as water, waste, and heat to retain value and move towards energy efficiency. This is connected to designing integrated solutions with metrics, IoT, and big data in mind. We are quite successful at doing so in Sweden, and this will become more common practice everywhere.

Many practices are responding to different principles of the circular economy. For instance, some manufacturers provide an array of different kinds of metallic fixation products for timber construction systems that allow for easy disassembly. This enables increased use of biogenic construction systems and the possibility to reuse the construction or make changes.

The dominant practices are the processes for logistics and storage to scale up the upcycling and re-use capacity to respond to the demand and make it viable from a cost perspective. There are several companies that now clean and upcycle re-used bricks on a larger scale. This correlates to the markets that offer used products for reuse or upcycling. Developers are starting to make early estimates of how much CO2 savings they can make by scanning the stock of available products in an early design phase to comply with their CO2 roadmaps, but they also start to see a monetary benefit from it.

Other significant practices are the use or integration of biogenic materials used as insulation or components in inorganic compounds such as hemp and clay insulation that can be part of a cascading scheme in a circular economy. Also, practices involving adobe and tamped clay are getting more popular considering that they can be extracted locally, easily ground, recycled, or brought back to nature once used. There are also examples of modular practices where whole facade elements and load-bearing elements are being re-used with positive ground-breaking results, yet on a pilot basis.

In terms of built environment design, how do low-carbon, upcycled, and recycled materials influence architectural and design outcomes?

There are many aspects in which these materials, or rather, products, redefine the design outcome. First of all, it takes more time and planning as we need to apply ”new" methods, build capacity, and collaborate way more. It requires more cooperation between actors concerning knowledge, warranty-related issues, and investigations.

Another challenge is complying with standards, maintaining life expectancy, and fulfilling a wide array of technical requirements. Such challenges raise questions about how different actors can share risks, how we value different design criteria, and how policies and regulations can be developed to support the use of new solutions.

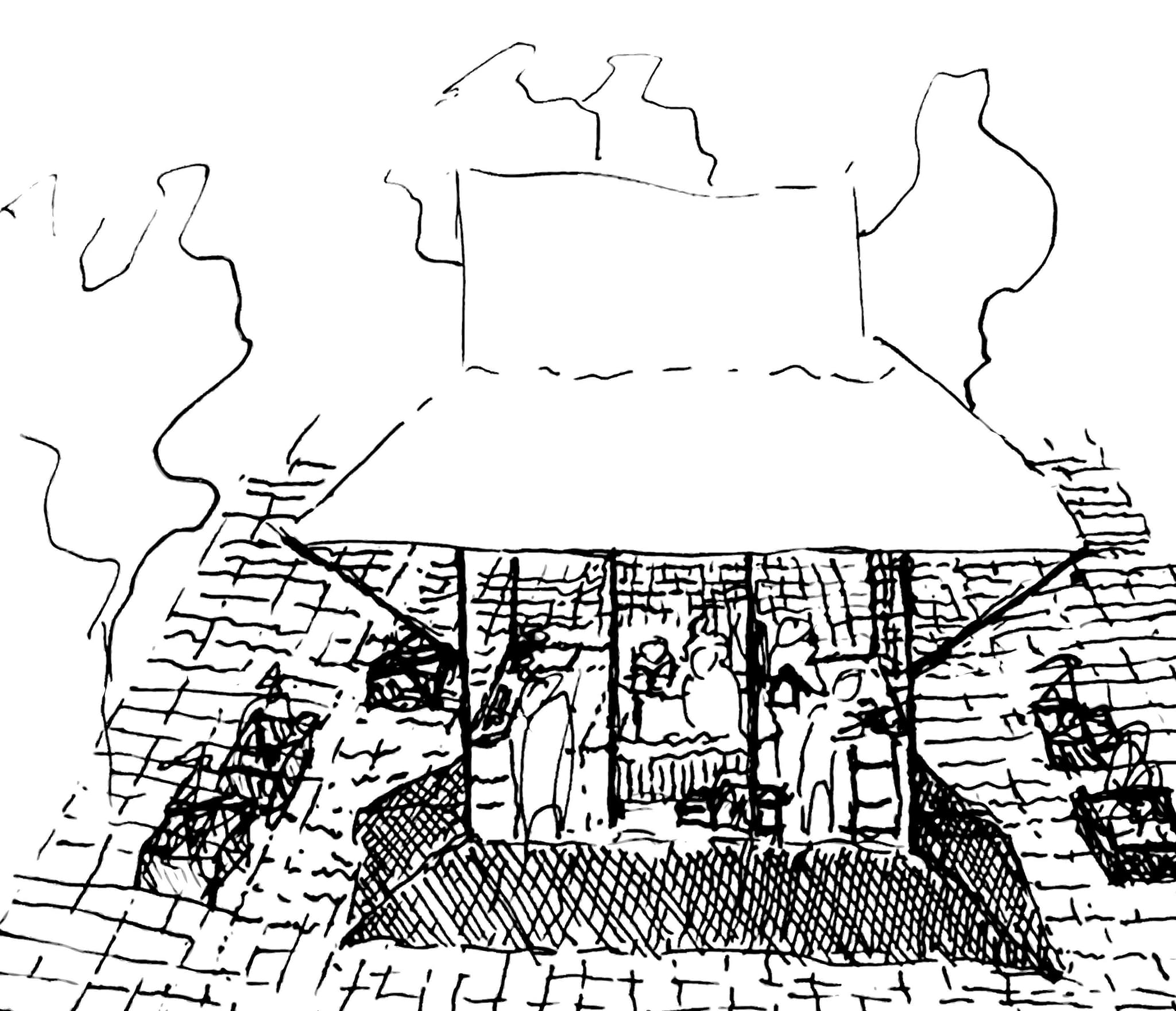

Dicksonska palatset by Liljewall arkitekter is a good example of upcycling a whole project by taking a holistic approach. A former private residence built in the mid-19th century was, by the mid-20th century, sold to the city of Gothenburg, which implied trade-offs in architectural qualities and the demolishment of two beautiful conservatories. In the hands of the city, it was used only on occasion for the last seventy years.

Today it has been transformed to host a wine cellar, a restaurant, a venue floor, and offices. Original details and windows have been restored, and the conservatories have been reconstructed in the original Renaissance revival style.

This is an example of how we can upcycle the existing building stock to retain its value by bringing forth former qualities and allowing new functions and tenants so that the building is being used rather than standing vacant.

Compared to a new construction, there were trade-offs made with respect to the historical value as well as the technical limitations of the building itself. For instance, the ventilation and cooling systems could not provide the same quality as new construction or accessibility to digital services, but improvements in improving and restoring the roof, chimneys, and skylights are being made.

How are the roles of decarbonized, upcycled, and recycled materials evolving in modern architecture? Can you share insights on the research and development in this space?

Low-carbon materials have a great role to play in the built environment. They are often locally sourced bio-based renewable materials. We are starting to see more manufacturers of hemp, hay, grass, seaweed, and clay products, for instance, in the Nordics. The wooden architecture with load-bearing systems of cross-laminated timber, glue-laminated timber, and laminated veneer lumber is continuously increasing. These materials do not only have a low carbon emission footprint; they also have superior properties that naturally regulate indoor air temperature, quality, and humidity, as well as having recreational value for our health.

The recycling of materials is the last resort in the circular economy before combustion. Nevertheless, when items become obsolete and cannot be repurposed on a larger scale, they might be recycled. Finite materials such as metals and glass can be recycled an infinite number of times. By recycling them instead of extracting new virgin metals from iron ore or sand for glass production, a lot of carbon emissions can be cut as less energy is needed in the production process and value can be retained.

Can you share a specific buildingwhere circular design principles were paramount and where the use these materials made a significant difference?

Gokartcentralen in the neighbourhood Gullbergsvass in Gothenburg is an example where Liljewall manages to transform a building and increase its value by replacing the former low-quality terminal facade with a new one with re-used bricks mounted for easy disassembly. It was paramount for the client that the new facade could be re-used in the future, as the future of the building stood uncertain in the development of a new neighbourhood.

This allowed existing tenants to be relocated within the terminal building with an improved location towards a new square. Using low-carbon re-used bricks and a special Dutch facade system guarantees easy disassembly if needed.

By using re-used bricks and design for disassembly, it increased the building's value and the value for the tenants, kept emissions to a minimum, and contributed to a new beautiful facade that will endorse the site, contributing to social sustainability.

When comparing traditional building materials with low-carbon, upcycled, and recycled alternatives, what tangible benefits and possible downsides have you observed or anticipated?

Traditional building materials are characterised by highly intensive fossil-fueled production, often being marketed as not needing maintenance, and often harmful synthetic or compound products that are difficult to reuse or recycle and not possible for nature to use as food. They are based on a take, make, and waste model. Such materials are typically plastics that we can find, for instance, in paints, installations, furnishing, windows and doors, adhesives, or insulation. These products are not people or planet-friendly and cannot be part of a natural circular system; they are waste and pollution.

There is a challenge when using biogenic or locally sourced materials, such as clay. For instance, to choose the right kind of timber. A piece of old wood timber is manyfold more sustainable than fast-grown young timber. We also need to consider how biomass is being harvested and whether cascading products are used at their highest value at all times. Having that said, we need to take into account that leaving dead biomass in the forest is to be considered, as it can have a considerably positive impact on biodiversity and carbon sequestration. This also means avoiding clear-felling and deforestation.

Using low-carbon materials, up-cycled or recycled materials often implies more care, maintenance, and consideration when it comes to building complex projects. This can be a good thing, as they last longer, provide work, age with a nice patina, and provide healthier environments. The initial cost can sometimes be higher, but in the long run, it is way more sustainable as you retain the value. At the same time, there are examples where large savings have been made even initially when up-cycled materials have been used, for instance.

How do you foresee the evolution of circular economy principles within built environment design over the next decade?

I believe the principles of the circular economy are here to stay and remain more or less the same. These principles will help us move towards a regenerative society. In the short term, we will likely see an increase in keeping products and materials in use at their highest value as well as designing out pollution and waste. We will be going from a consumer society to a service-based society as resources are scarce and materials will be more expensive. Labor will become cheaper. More products, such as installations and building operations products, will be rented as products or services.

Regarding the design process, it will be common to put more effort into early investigations such as monitoring, inventory work, documentation, and data analysis of existing stocks. There will also be a more pragmatic perspective on how the built environment will look like as the design will most likely change more often as the design process continues due to uncertainties in what materials are available at what time. This might lead to a mind shift in regard to what we value. We will also see an increase in cascading products; new low-carbon bio-based products are continuously coming out on the market.

In a more long-term perspective, I am sure we will move towards restoring natural systems. This is deeply connected with climate adaptation and the roots of circularity towards a regenerative society. Different actors already have knowledge and methods to address this; we just need to collaborate and build capacity, platforms, and policies to integrate systems thinking on all scales so that we can achieve systemic change and harvest as many synergies as possible.

I am hoping to see more new, healthy circular business models that collaborate across the whole value chain to retain the highest value at all times. I hope to see policies in place that support small-scale businesses to scale up. In regards to the design process, I am curious about what kind of mind shift in the perception of the built environment will come out of this. Can the re-used built environment get a higher status, such as antiquities, considering the quality and history of the products we use? I believe handcrafted and bespoke designs will become more common as a natural increase in demand for circular jobs.