Could you elaborate on how the themes of deep ecology, kinship, and interconnectedness manifest in your work, particularly through your engagement with plant-based materials?

I view what I make as a co-creation. All of my work comes from a spiritual and philosophical foundational belief that all life on earth is kin, coexisting together. All life on this planet intersects, influences, and affects all others. We are part of a global ecosystem and each being has an inherent worth. I don’t believe that human life is worth more or less than any other form of life. I believe we all need each other. We need diversity of all kinds. We need diversity of people, we need diversity of animal life, we need diversity of plant life and fungal life and slime mold life and the list can go on and on.

In my work, I am highlighting and actively exploring this idea of kinship through collaboration and appreciation of that which is other than me. I am fostering more connection with the larger biosphere through engagement with a variety of natural materials. These materials can be plant fibers, clays, ochres, botanical pigments, animal fur (responsibly and humanely gathered), human hair, discarded shells, and more.

In living and working in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay region, how does the historical and ecological context of this area influence your artistic and design practices?

I seek immersion as a pathway to kinship through observation and exploration, whether I am working within my local region or elsewhere.

At home, I look to our regional native plants, the landscape and the shoreline as a source of inspiration and collaboration. Some of my work is inspired by shapes, forms and colors commonly found in this region. Looking closer, I examine components of the material structures of the local flora and fauna, such as the calcium carbonate found in the eggshells used in some of my paintings. I am interested in the possibilities for biomaterials found here at a local level and how this can contribute to the circular nature of my work and a deeper, more intimate exploration of place.

I also want to acknowledge the indigenous inhabitants of this region prior to European encroachment: the Susquehannock and Piscataway peoples. It is my goal to further educate myself on this area’s indigenous history, particularly in relationship with native flora and fauna.

I also spend time volunteering with the nearby Middle Patuxent Environmental Area (MPEA) Plant Propagation Project, familiarising myself with our area’s native plant species and aiding in increasing biodiversity in the region through propagation of native plants, clearing of invasives and planting more native species within the parkland.

Similarly, when I travel, I seek immersion to make connections with the locales I am in and create something from a sense of place. I recently spent time in an artist residency in Spain (Joya AiR) and while there, I sought to introduce myself to the land, taking walks and examining the soil, the trees, herbs, and other plants.

I was educated by the residency’s founders on the history of what is traditionally found growing in the region, as well as local climate concerns. I then gathered up area earth to create pigments, mixed with local egg yolk as a binder to make a natural tempera paint which I used to create painting studies based on area motifs and flora. I also gathered plant fibers and sticks from around the residency property to create a weaving. Being that Joya was in a time of severe drought, I sought to use as little water as possible in the work I created, saving water from my shower to soak the fibers in for the weaving before pouring it atop thirsty plants.

Your practice involves a circular system of working with materials. Could you describe a specific project that exemplifies this approach, highlighting the sowing, growing, harvesting, and processing stages?

I seek to incorporate circular practices as much as possible. With my corn husk sculptures, I sowed the seeds and nurtured the plants to maturity, harvested the corn and worked with the husks and silk to create sculptural forms.

Similarly, I created a trio of experimental garden weavings that incorporated oregano stems, corn husks and other materials from plants sown and grown in my home garden, combined with hair from our dog Kira’s routine brushings that had been spun into a yarn.

The botanical inks and lake pigments I’m working with, such as those made from Dyer’s chamomile and hopi black dye sunflower, are produced through sowing, growing, picking, and processing into evaporated ink and/or lake pigments.

You mention an exploration of spiritual and philosophical curiosities within your work. How do these curiosities inform the selection and treatment of materials in your projects?

Spiritual and philosophical curiosities explored relate to themes of deep ecology and kinship shared with our global ecosystem. Each being on this earth, be it plant, mineral, human, or other, has an intrinsic worth and purpose in and of itself. I spend time with the materials I work with and find that the selection organically happens. It is often a meditative and intuitive process and practice.

I see it as a co-creation in kinship with these plants and materials. My curiosity in getting to know a plant, mineral or other material (such as discarded shell, fur, or hair), leads to a kind of spiritual process of listening and being guided by a sense of intuition into the emergence of a new form.

Your work investigates psychic landscapes and liminal spaces. Can you discuss a piece specifically addressing these concepts, and how you used natural materials to convey these ideas?

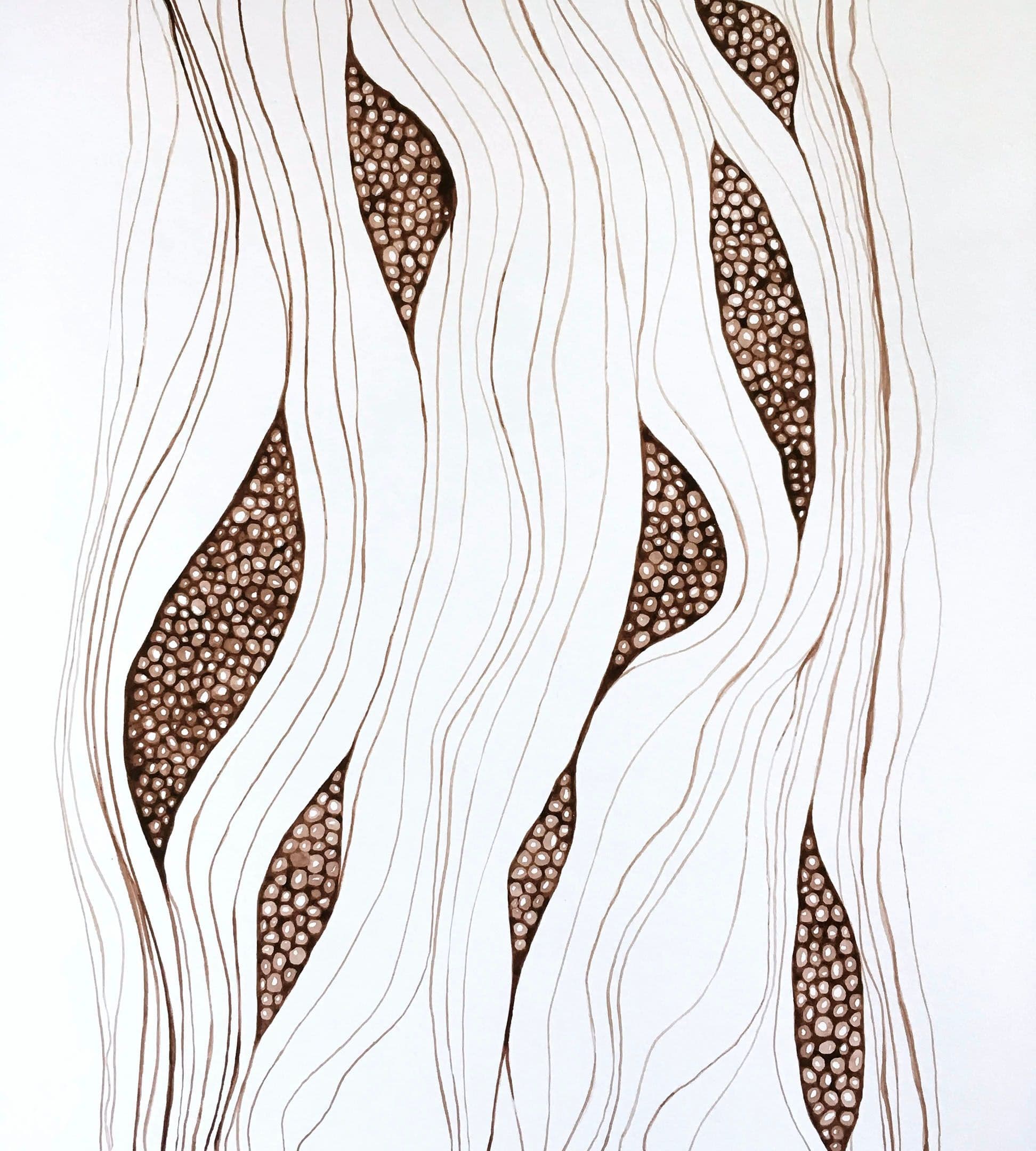

All my paintings can be said to be an exploration of psychic landscapes and liminal spaces. I utilise a grid to map out an area first and then I sort of let go and flow, allowing myself to be carried around that space. My brush bumps up against the grid lines and flows through them. In this dance, I am meditating on ideas of containment, constraint, categorisation, identification and binaries in juxtaposition with flowing through the grid, breaking through the binaries and moving into and through the spaces in between.

In my most recent painting series “Aether,” the materials themselves may be seen to represent a sort of binary being shades of black, created from wood ash, and white, created from egg shells, though I am not seeking to be literal here in any sort of narrative. For me, this exploration is intuitive and personal and not so easily translated.

Everything I create may contain a variety of meanings or symbolism, though I prefer to leave all of that up to the viewer to experience in their own way.

The use of sustainably gathered materials is central to your practice. How do you navigate the ethical considerations of foraging and harvesting?

I take direction from Robin Wall Kimmerer, as outlined in her book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, where she advises:

“Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them. Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life. Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer. Never take the first. Never take the last. Take only what you need. Take only that which is given. Never take more than half. Leave some for others. Harvest in a way that minimises harm. Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken. Share. Give thanks for what you have been given. Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken. Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

This is my approach to foraging and harvesting.

You’ve expressed an interest in the beauty of imperfections and natural cycles. How do these inspirations influence your creative process, from conception to the final artwork?

In letting go and letting the work flow forth, I am letting go of the need to have a perfectly drawn-out plan of execution. I am willing myself to work through the process and allow it to emerge without too many attachments or preconceived notions and to pay attention to when it feels finished.

Personally, over the years through many stages of my art practice, I have found it difficult to see a project as finished. I always saw room for improvement. Yet, in any life cycle, there is no final perfect form that is achieved. Life keeps on moving, getting nicks and scrapes and weathering with age. Life cycles from formation to decomposition and back again.

So, in this sense, I am allowing room for creation and then pause to allow a work to have its life beyond me and be what it may be.

Given your use of a variety of natural materials, from food scraps to minerals, how do you experiment with and decide upon the right material for each project?

I start with the materials first and let them lead the way. Earth may be processed into pigments to further become a paint and botanicals may be made into inks to be used as a wash of color on paper or on unprimed canvas. Plant fibers may be made into cordage that could be used in weaving.

I typically gather up materials, sit with them, and then intuitively proceed into what they will become. It’s a very organic process and it’s a process led by curiosity and exploration of the forms and textures of each material and how it may be best presented to express itself.

Can you share insights into how you prepare and transform these natural materials into lake pigments, evaporated inks, thread, or sculptural elements, and the challenges you face in these processes?

For many plant materials, you may start off creating an evaporated ink - basically cooking the pigment in a pot of water on a stove at different length intervals to get different concentrations of color - and then I may add soda ash which, for example, really brightens the yellow color of dyer’s chamomile.

A lake pigment process is more complex and takes some trial and error. You start with a dye bath as in the evaporated ink process and add solutions of alum and water and then soda ash and water to make an insoluble color pigment from a plant extract. The amount of alum and soda ash solutions added depends on the plant you are working with. I am still experimenting greatly with this process!

I am also working with raw plant fibers (sometimes purchased and sometimes gathered), spun into thread using a drop spindle or twisted into cordage. I then weave these materials together free-handed or on a small frame loom. I plan to work further with larger looms in the future and create more basket-like forms.

I am interested in traditional means of processing these materials, such as hand-spinning and pigment extraction as I feel that it forges a closer, more tactile relationship with the materials used. Utilising these processes to obtain pigment, inks, thread or cordage is definitely labor intensive and requires a lot of patience, as well as trial and error, however, I find that the process is incredibly rewarding. In a way, “it’s the journey, not the destination” could be a mantra for me.

The process forges a deeper kinship with that which lives around me and in turn a deeper kinship with this earth ecosystem we are all a part of.

Reflecting on your artistic journey, how has your practice evolved over time, particularly in terms of material experimentation and the themes you explore?

I find that I am reaching back in time and making a connection with my child-self.

In my early years, I would gather all kinds of plants from our yard, making “potpourri” or “perfume.” I would wade into a creek bed and gather up mud, forming it into little pots. I would make crowns and rings from dandelions and other little flowers. My current process harkens back to that childhood wonder, being outside immersed in observation, exploration, and discovery of the world around me.

I love my current practice. The process is rich; it’s play, it’s alive, and it’s rewarding in and of itself like the process of cooking can be so rewarding even before the end result of a meal. What ends up emerging has a rich history and is part of a longer journey; it has a story and I am a lover of stories. Possibly I am seeing my practice as a mission of sorts, to help tell the story of our other-than-human kin.

Through my work, my exploration and dedication to getting to know these plants, through their life cycles, their forms, what they need to thrive, what prevents their thriving, what they look like when healthy (or not so healthy), what other beings feed on them, who and what they nourish, and how they interact with the human body, I am discovering how to honor and care for them as they care for us. This is what I call kinship.

As a plant’s life cycle winds down to the stage of decomposition or composting, keeping some parts of the plant to make ink, paint, weavings, or sculptures is a secondary way to carry on their life cycle into birthing something new.