How do you envisage the future of biodesign influencing the sustainability and functionality of architectural projects?

Integrating bio-based materials within our practice begins to answer multiple major issues we currently face. Firstly, Bio design can bridge gaps in our relationship with materials. We often think of materials as non-biological, static, and disconnected elements from our living environments. We only choose them from an aesthetic perspective.

But more and more, we are beginning to realise the benefits of re-engineering some of these materials to enhance their properties to behave as bio-reacting elements, creating cleaner and healthier living environments. Through circular systems, we can support communities affected by natural disasters, economic hardship, or political factors by integrating systems that use local resources, allocate jobs, and reduce CO2 emissions and waste.

We can already see the deployment of this design approach in projects such as MycoHAB by Redhouse Studio. MycoHAB focuses on using invasive bush plants from Namibia as substrates to cultivate Mycelium, which will then be used as structurally sound compacted material to provide affordable housing. That is exactly how I envision the future, a future where we no longer see ourselves as the only living beings on this planet. With this perspective in mind, we can work towards a symbiosis between the humans living in these spaces and the environment itself.

With advancements in biomaterials and 3D printing, what opportunities do you see for creating more adaptive and responsive living environments?

Thanks to the advancements in 3D printing and the adoption of interdisciplinary research within our field, we are seeing a revolution in how we look at materials to build our environments, and how these are looked at beyond shaping experiences.

Looking at materials from the molecular scale, we can identify their natural properties, enhancing them to self-heal, act as photo-bioreactors, purify our air, and respond to heat or humidity. One of the institutions that started this biodesign journey for me is the Institute of Computation Design at Stuttgart. They have been pushing the frontiers of our built environment by researching and re-engineering wood that can close or open itself as a response to humidity.

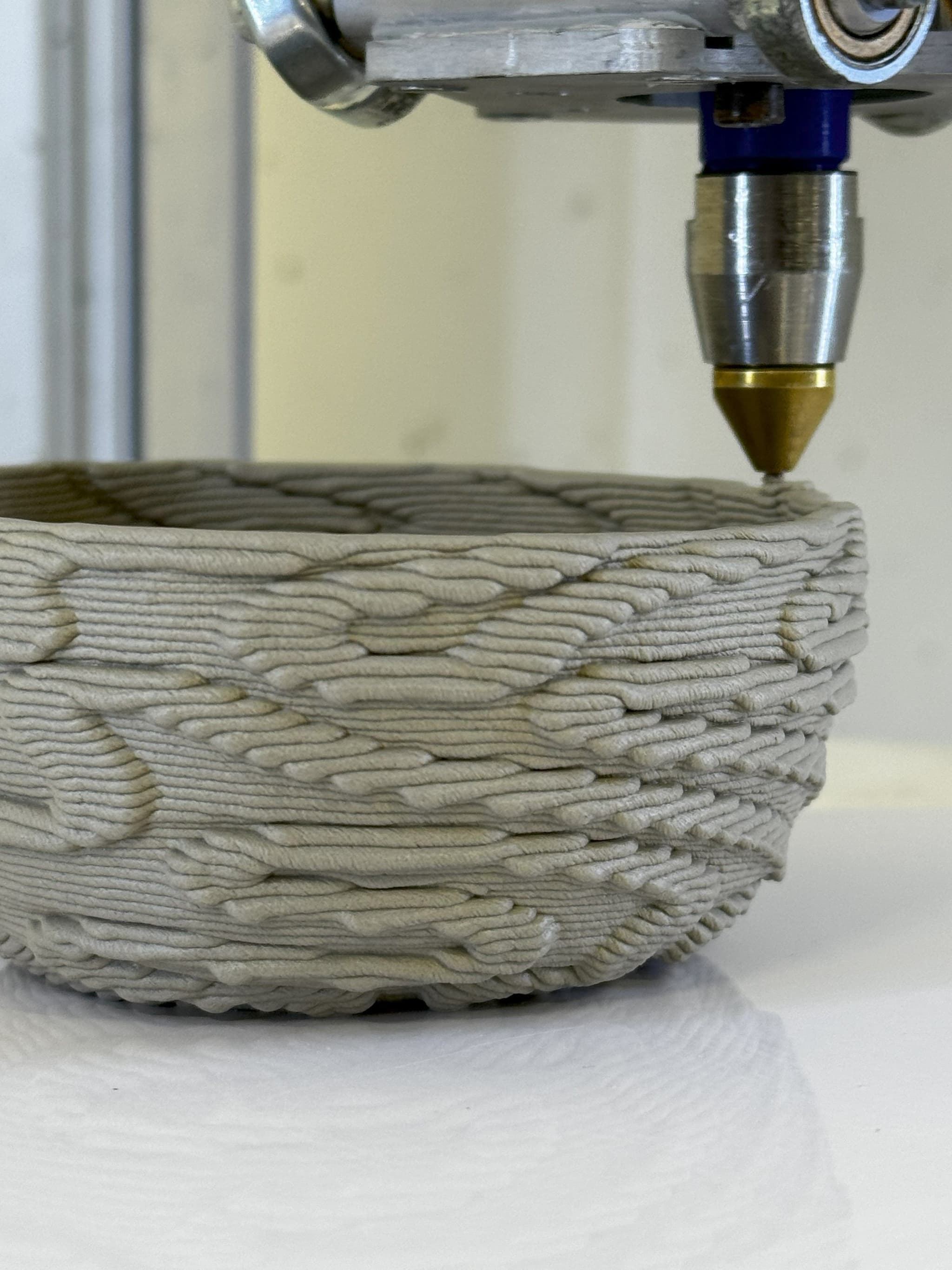

For this reason, biodesign plays a huge role in our future as their methodology allows us to create a symbiotic and adaptable environment for all living beings. Coupled with the increasing development of 3D printing, in scale and production, we can start shaping a future of dynamic and interconnected systems that improve our health and living experiences and leave behind the static, physical elements.

That’s exactly the work we are trying to do at the MS. Health and Design at the School of Architecture and Design at New York Institute of Technology. We envision a future where materials can react to our internal bodily changes through natural and artificial sensors and can improve our mental and cognitive condition.

Reflecting on your teaching methodology, how do you instil the importance of sustainability and ethical material selection in your students' design processes?

It starts by redirecting the goal of our profession from the superficial, geometrical, and aesthetic to a human-centred experience that enhances health and well-being. At the MS. HD, we focus on teaching them first the adoption of design thinking and systems thinking mindset to understand holistically how their design goals are affected by different factors through different domains.

Through this thinking process, we hope to instil in them that our built environment and spatial experiences are affected beyond the materiality and spatial factors we’ve been introduced to in our academic years. We believe that to impact this world we must consider the relationships humans have with their cultures, interpersonal behaviours, mental and human health, and spatial conditions and how these can be built into a sustainable ecosystem towards positive futures. In the end, Biodesign and sustainability goals are the product of our beliefs.

What role do you believe digital fabrication technologies will play in the future of designing for health and well-being in built environments?

Digital fabrication technologies will play a huge role in our built future. Digital fabrication tools have allowed me to have a closer relationship with the art of making. The architects of our past were master crafters, understanding very closely how to shape, control, and affect materials to last perpetually in our world.

Over time, the demand for mass-scale production and automation of industrial fabrication processes forced us to create ready-made building components such as materials, breaking our understanding of how we can let them help us shape our spaces from the initial design phases. However, I believe designers are now empowered to mend this relationship by utilising advanced tools like robotics.

Today, robotics is used to 3D print, build discrete components, 3D knit, and more. In a way, you can say we are on the path to becoming master crafters and again–digital crafters. Yet, for me, the most exciting part is that to become very skilled in these tools, we must adapt by learning other disciplines such as computer science or biology to integrate them within our design processes.

From your perspective, what are the most significant barriers to integrating biodesign concepts into mainstream architectural projects, and how can they be overcome?

I think the most significant barrier is convincing businesses and architectural practices to integrate this design thinking and methodology within their practice. The first major problem is that most studios and clients do not see the integration of bio-based material projects as profitable. We have to prove to the public that integrating biodesign methodologies can have sustainable, resilient, and engaging effects in our world and communities in the long term.

In addition, Biodesign work is still in its infancy within the architectural field. This does not mean that the work doesn’t exist - there are a few office studios and mostly universities pushing the research forward. To overcome this, our leaders within practice and academia must find ways to collaborate to bring this research to a pragmatic real-life application.

Secondly, there must be data gathered from this collaboration. Suppose we argue that bio-based materials are sustainable or circular. In that case, we have an obligation to prove it to the public through statistically significant data that shows the effect on air quality, energy use, CO2 emissions, and potentially create circular economies if approached correctly.