Your projects often reflect themes of survival and resilience as metaphors for social processes. Could you explain how you select natural phenomena that parallel specific societal issues?

Usually, I get to know about a phenomenon through investigation, in documentaries, or just by accident. Generally, I’m interested in the diverse strategies of growth, survival, and resilience. The first selection occurs there. I get more involved with the theme and make some studies. During the process of translating what I found into art, I start finding parallels or think about how this could influence the understanding of our human society and life, considering that we are part of and connected to the nature surrounding us.

In the creation of your series on the mangroves of Juan Díaz, how did you determine the most effective artistic methods and materials to represent the carbon retention data provided by chemist Olmedo Pérez?

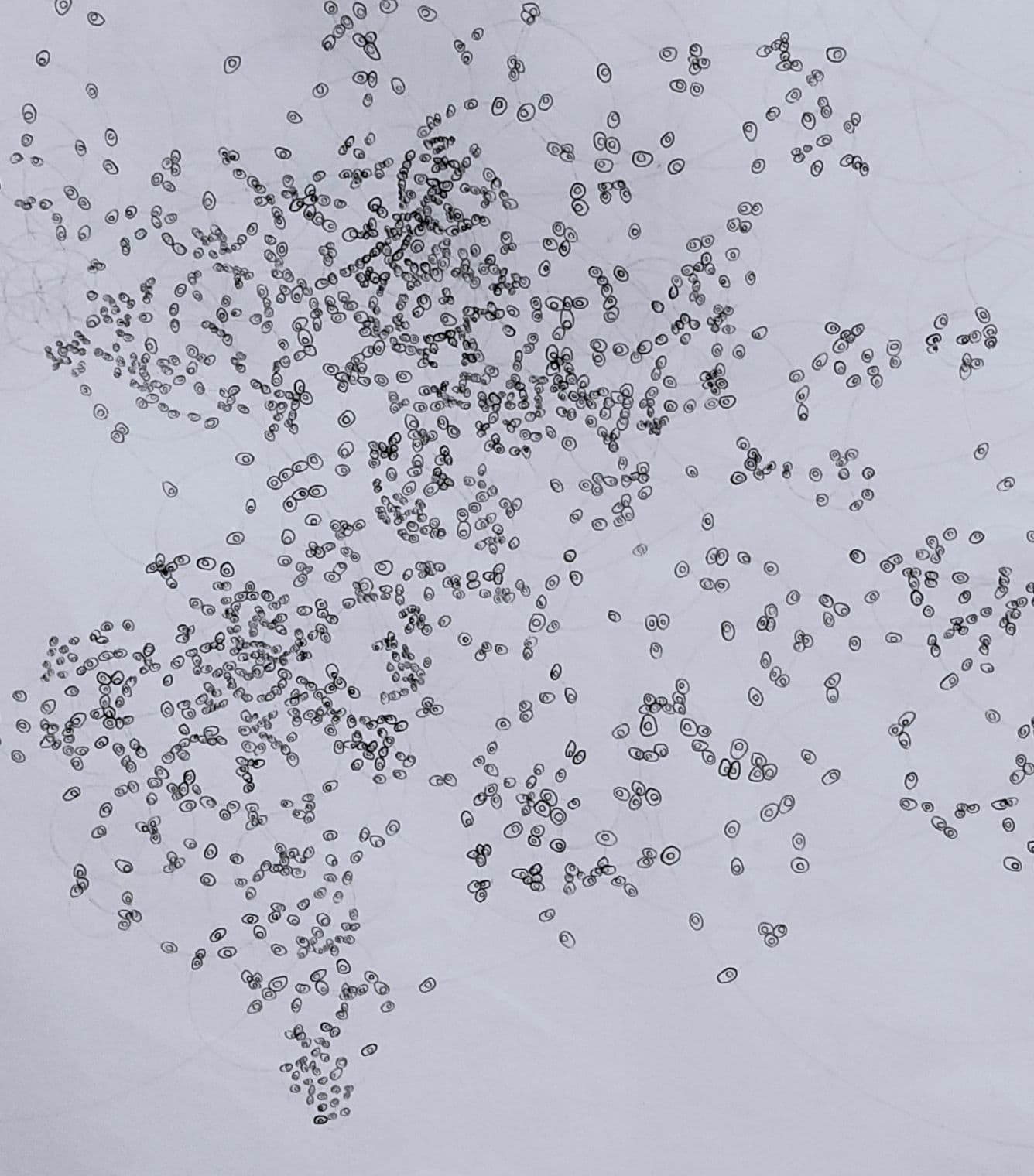

I created these drawings during a residency in Panama and had the chance to visit the mangroves with Olmedo. I was very impressed by the deterioration of these mangroves; there was a lot of waste there. On our walks, I found some burnt mangrove trees and took some carbon with me. Olmedo’s investigation was about the mangroves' capacity for retaining carbon (blue carbon). He showed me how they measure how much carbon can be maintained and how it was doing in Juan Diaz. For me, using carbon to make ink for this series of drawings was logical. It was very meaningful for me.

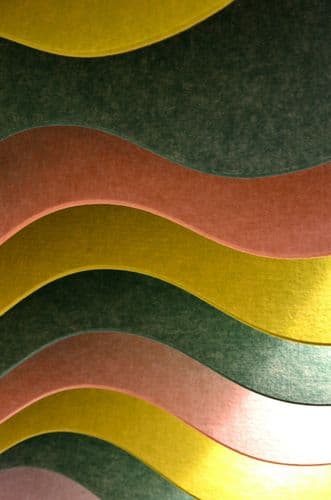

Also, the drawings were my way of understanding Olmedo’s investigatio, while chemistry is quite difficult for many to understand. I wanted to express my understanding in these drawings so they could help others to grasp the topic. The drawings are composed of symbols of chemical connections, and the covered areas represent the percentage of retaining capacity found by the scientists.

Can you elaborate on your choice of materials, such as plantain fiber and aluminium wire, and how they align with the themes of conservation and restoration in your art?

Materials have always mattered to me in my three-dimensional pieces. Even when I was a student, I liked to experiment with different materials, exploring the sensations and emotions they could convey. I did many works with paper, fallen wood sticks, or leaves, as I was always concerned about not using harmful materials. It was always a struggle, as the art market seeks durable artworks that won’t change colour, shape, or texture over time. So I started to investigate ancient techniques of making paint, textiles, etc., to ensure my artworks would last, even when using natural materials.

Often, I found myself obliged to use common materials. Wire or wood, in many cases, are indispensable for building structures, but I try to avoid them as often as possible. The installation desapercibi2/struggle, made of aluminium wire, was an exception, as it was created for the Central American Biennale. It had to be transportable and durable, as it now forms part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Art of Fundación Ortiz Gurdián in León, Nicaragua. I wasn’t happy about using only industrial wire, but I wanted a durable and mouldable material to create skeleton-like structures. Wire works great to create large volumes with less material, so at least I was saving a bit of material.

Now, I’m focusing on investigating “new,” eco-friendly materials. Recently, I found that plantain fibre is a great material, as it is a waste product of a large industry here in Nicaragua. It’s very versatile, and there are many traditional uses for it, such as rope, rustic fabric, etc., and even very fine fibres with a hair-like texture. The traditional methods of obtaining fibres are very labour-intensive, and there is no semi-industrial production of fibre here like in other countries. So I’m trying out different ways to transform the raw material into something that inspires me to create.

You have described using repetition, expansion, and occupation of spaces in your work. How do these elements specifically contribute to the narrative of community organisation and social welfare in your installations?

Society is a construct of many different social groups, many of them minorities or marginalized. Groups are formed from individuals, through a feeling of belonging because of one or another aspect. Community organisation, in my opinion, works best as basic communities, where mutual care is the main aspect of togetherness.

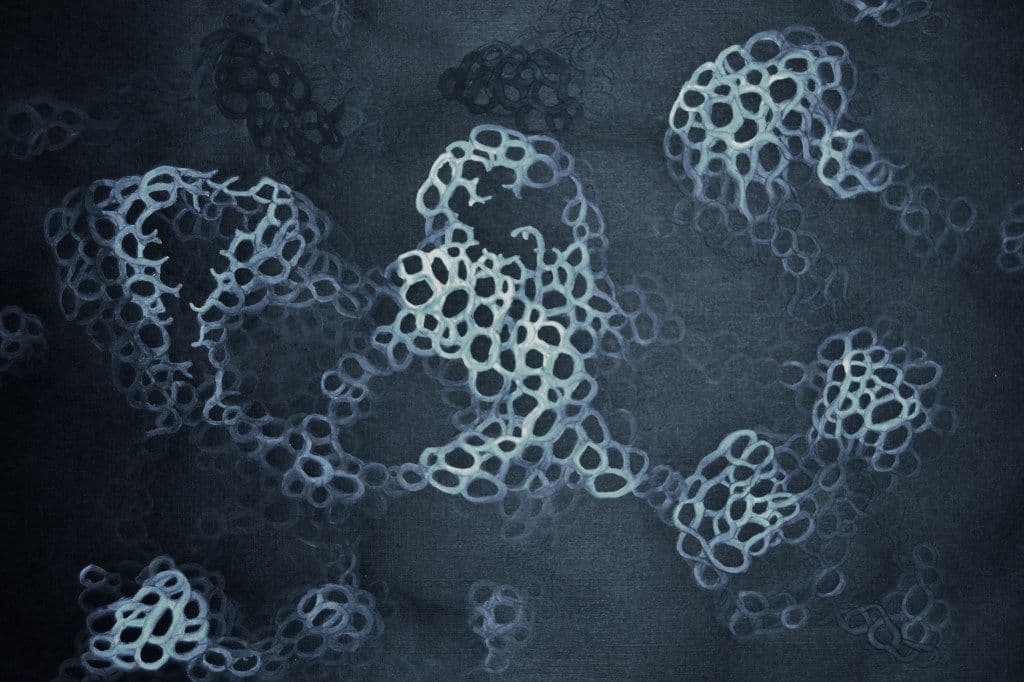

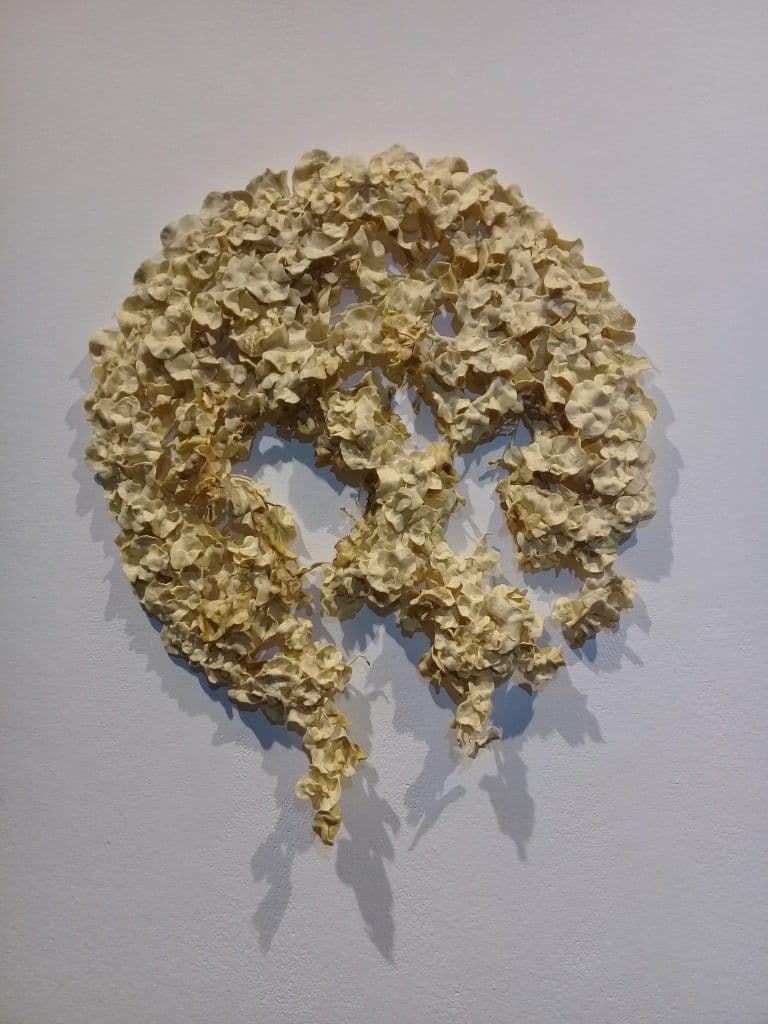

The elements that form my installations, as individuals, seem fragile, weak, and small. By forming groups, they gain space and significance, eventually occupying the entire exhibition space. For me, that’s how an emancipated society should work.

Your work involves a significant manual process that showcases imperfections and irregularities. How do these characteristics influence the viewer's interpretation of your pieces?

Humans are imperfect. Perfection in art is usually achieved through technological processes or due to outstanding skills and dedication. For most viewers, this is very far from their own lives. By accepting my imperfection and allowing the manual process to show, I hope to involve them as human beings.

Revealing the artist behind the piece opens up possibilities for dialogue, and that dialogue with the audience is very important to me.

How do you balance aesthetic considerations with your message about environmental issues and social change in your artwork?

I want to send messages of hope, despite the many pessimistic news reports about the environment, society, and politics. I am convinced that every change begins with positive emotions, with hope and love. By creating aesthetic and eye-catching artworks, I first want to capture the attention of these positive examples.

I like to evoke thoughts like, ‘What if we acted like fungi, like a big organism composed of many individuals? What if we accepted that life is a pansimbiotic system?’ We interact with, influence, and are influenced by every other living being, so we should respect them all. Pansimbiotic health is more important than individual health. My aesthetic is the vehicle for my message.

Given the complexities of interpreting scientific data through art, what challenges do you face in ensuring your interpretations are both accurate and impactful?

This is a difficult question and a point I’m always working on. As I prefer silent discourse instead of direct messages, it’s difficult to ensure everyone interprets the work as I do. I like discussing my art pieces with visitors.

For me, art cannot be the solution, but it can be a starting point for conversation and change. I know I can’t speak to everyone, but through aesthetic decisions, hints in form, and the title, I try to evoke thoughts and feelings that point in the right direction.

The concept of 'protection communities' in your installations is intriguing. Could you discuss how you conceptualise and physically construct these communities within your exhibition spaces?

Every living being needs protection and care; these are basic needs of life. The construction of protective communities occurs almost automatically, as I start every installation by imagining the individuals with their peculiarities and needs. Since all parts are made through manufacturing processes with variations in form and size, each one has its own ‘personality’ to me. When I enter an exhibition space, I begin imagining it as a habitat and continue constructing groups or communities in different places. I make sure these groups are balanced, so the individuals seem to support each other and would be able to survive and spread if they were real living beings.

Some works also address ruptures in social structures, like in “Faltan tus estrellas” (Your stars are missing). I began by imagining an intact community, inspired by lichens, and then disrupted the form as if by an external force. The ‘broken pieces’ settled throughout the exhibition space to form new communities.

Looking forward, how do you plan to evolve the thematic and material components of your work to further explore and comment on societal and environmental issues?

The topics for my artworks usually surge from the processes I am working on at the moment and current events. As I am focused on symbiosis and equal and peaceful coexistence, I think they will develop in that direction.

Further, in this context, my experiences as a mother—this basic coexistence and interdependence—might provide an interesting topic that could open another perspective on the theme of mutual care.

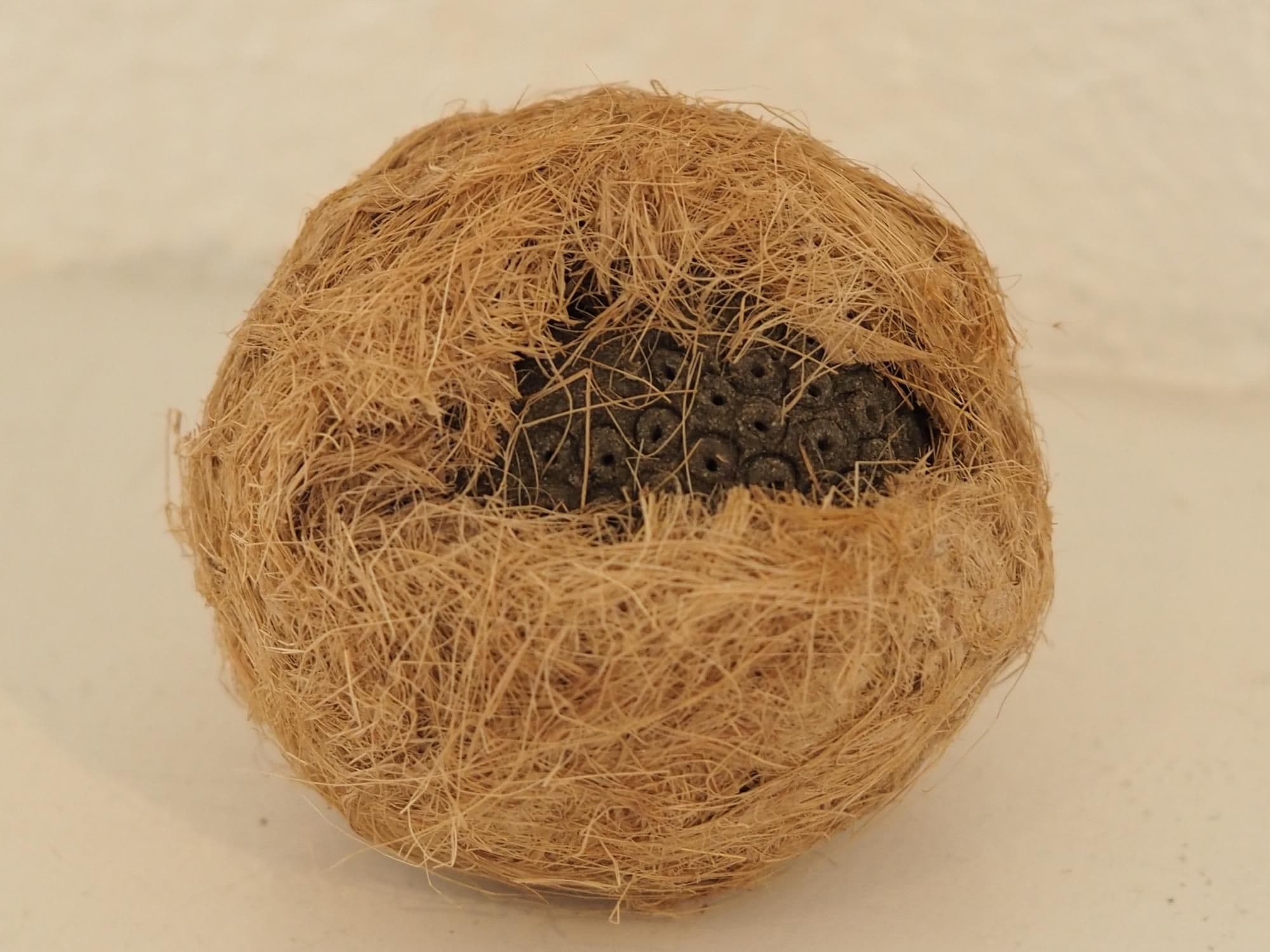

Concerning my material research, I will continue with the different processes I’m exploring, such as natural fibres and pigments. I’m also conducting experiments with mycelium to substitute common industrial materials like MDF, and I recently exhibited my first mycelium experiment. These investigations will continue, and I hope to be able to show them and relate them to current societal and environmental issues.