Key Points

- Cellulose is kept minimally processed: flexible, transparent, self-evolving, accepting fragility over hard stabilisation.

- Bacterial cellulose becomes a sensing skin, encapsulating electronics; dried only at the end to fix capacitive behaviour.

- Two-phase bioprocess: a rotary/air-lift growth phase boosts biomass, followed by static consolidation to preserve microstructure.

- New sourcing logic: think distributed cultivation (protocols, care, lineage) instead of centralised factories; classify by species, substrate, responsiveness, and care protocols.

Full interview with Vivien Roussel:

In both the shoe and the gamepad, form emerges from growth rather than construction. How do you navigate design intent when working with a material that self-organises?

It’s an essential question, as it touches on the central tension of my practice: how can one design when form is not constructed, but cultivated? I don’t believe that intention alone can compel matter to become what we imagine. Working with living material is, in a sense, a continuous dialogue between what we project and what the material chooses to do (a shift from control to negotiation). This research not only proposes a conceptual shift but is grounded in the development of a biofabrication process that enables living matter to be guided, constrained, and stabilised into functional forms over time.

Because the material is capable of self-organisation, I try to understand its internal logic: its metabolism, thresholds, and rhythms. My role is to shape the environment, adjusting oxygenation, nutrients, and shapes within the bioreactor so that the process can unfold according to its own coherence. The bacterium Komagataeibacter xylinum (part of the SCOBY consortium: Symbiotic Colony of Bacteria and Yeast) produces cellulose through fermentation, so rather than sculpting the material, I tune the conditions of its metabolic environment. In this context, morphogenetic design is not understood as a metaphor, but as a practical approach in which the designer operates on growth conditions, material substrates, temporal rhythms, and environmental constraints rather than on final geometry alone.

In the shoe project, the kombucha culture was guided along a predefined surface, gradually becoming more attractive to subsequent bacterial layers until the biomass accumulated and reached equilibrium. For the game controller - created with Madalina Nicolae - we accelerated the growth so that it could absorb electronic components within the living biofilm. In both cases, it’s not about imposing a form but about cultivating conditions of possibility.

Time becomes a primary design parameter in this approach. Instead of producing objects that are fully resolved at the moment of fabrication, the proposed bio-process allows form to emerge progressively through growth, transformation, and partial decay. The artifact is therefore designed as a trajectory rather than as a finished state.

I navigate between intention and self-organization, often by playing with uncertainty. I let the living system complete the gesture, and the form becomes the trace of an encounter between my intention (as a designer) and the metabolism of the material (kombucha), between what is conceived and what is allowed to emerge. It’s a new form of relation with the living matter, not just design “with” or “co-design,” but a design of cohabitation.

2. The bacterial cellulose in the shoe retains its transparency, elasticity, and tactility without any post-processing. What were the risks or benefits of rejecting typical stabilising treatments?

Refusing post-processing was a conscious choice, both symbolic and practical. The main risk was fragility: the material remains alive, it rehydrates, deforms, and continues to evolve over time. This makes control difficult, but that is precisely what interests me. By preserving its organic state, the cellulose maintains a certain flexibility, a humid transparency, and a troubling aesthetic.

Most industrial processes aim to stabilise, that is to say, to kill. Yet it is within this instability that the material reveals its expressive potential: its ability to self-heal, to transform, to bear the marks of time. By allowing the cellulose to follow its own metabolic logic, it retains a form of autonomy and escapes the usual logic of optimization, which assumes that an object must always remain identical to itself.

Unlike many others, I did not try to make the cellulose more stable, but to rethink the way objects come into being. Rather than assembling dead materials into a fixed whole, I try to create the conditions for a form to develop by itself, from a living matter still active. It is a way to stay close to natural cycles and to accept that matter, like life, is never completely finished.

I know there are industries that have mastered cellulose treatment for centuries, whether in wood or textiles. But I believe that today we must invent other approaches, less extractive and more respectful of the cycles of life. Recent advances in green chemistry go in that direction: they open the way to reversible stabilisations, integrated into metabolic processes rather than opposed to them.

For now, my PhD in design and biology leads me to focus on developing a reproducible bioprocess capable of generating forms through the growth of bacterial biofilms. This means staying as close as possible to metabolic mechanisms rather than aiming for industrial durability or technical efficiency. However, I am obviously interested in collaborating with partners who have expertise in cellulose to develop conscientious approaches to these complex questions.

On an aesthetic level, leaving the material alive often provokes unease. Many people feel disgust when facing its moist surface; others experience an almost carnal fascination (see the films of David Cronenberg). This discomfort reveals something deeply cultural, inherited from the hygienist movements of the twentieth century. Modernity taught us to fear the microbial and to associate it with contamination. It has protected us, of course, but also isolated us. By sterilising our environments, we have weakened our microbial diversity and created ideal conditions for zoonoses: those transfers of pathogens between species that thrive in artificialised environments. We need to relearn how to make room for non-humans, not out of morality, but to rebalance our living environments.

I try, therefore, to reverse this logic. Our optimised environments produce fragility because they reject complexity. We need to reintroduce a metabolic way of thinking into production: to imagine worlds made of cycles, layers, and relationships, where materials can disappear to feed other forms without producing permanent waste. This is why I grow my objects: not to domesticate the living, but to let it reintroduce complexity into design itself.

3. In your UIST gamepad, bacterial cellulose becomes a sensing interface. What properties made it viable for this kind of technical integration without compromising its living character?

Bacterial cellulose is already a sensory structure: a polymeric network produced by bacteria, naturally porous, hydrophilic, and reactive to humidity, temperature, and the molecules present in water. These properties, which are usually neutralized in industrial contexts, make it here an ideal support for a living interface.

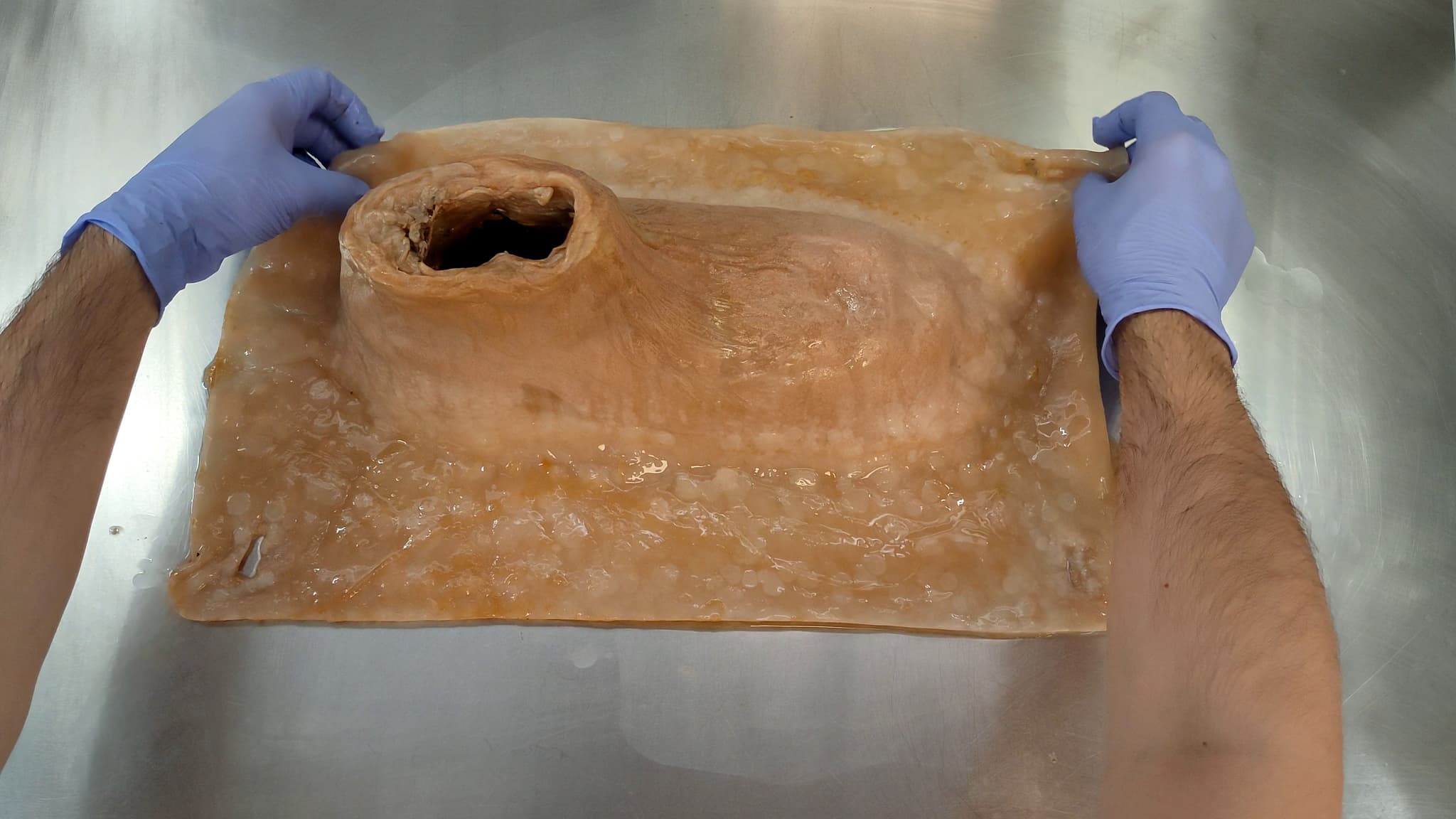

With the game controller, we did not try to add sensors but to work with the material’s intrinsic capacity to grow, absorb, and envelop. Since kombucha grows on the surface, it eventually suffocates itself by limiting the exchange of oxygen and nutrients. We took inspiration from aerosol bioreactors (fig. 3), which diffuse oxygen from above, to prolong growth and allow the biofilm to directly absorb the electronic components. The material thus becomes both skin and circuit, actively contributing to the sensitivity of the device.

At the end of the process, the cellulose is dried to stabilize the capacitive sensors, which “kills” the bacteria and fixes the biofilm. This tension interests me: the controller carries the trace of an organism that once lived, of a material that has passed from the living to the functional. The goal is not to make life useful, but to show how it can think with us through matter.

Finally, the controller is compostable: the electronic components can be recovered and reallocated to other prototypes. In a context where metals are becoming scarce, it is essential to rethink our relationship to matter, whether mineral or living. We must regain a sense of what we handle and recognize the energetic, human, and temporal value contained in each element. It is a way of reintegrating technology into a real cycle, rather than a political or purely speculative one.

4. Could you describe the bioreactor setup you used to grow these artifacts? What parameters were most critical in directing the final outcome?

The system I use is similar to a rotary drum bioreactor, adapted for the culture of Komagataeibacter xylinum. My bioprocess stands out due to the hybridization of a rotating drum bioreactor system with a static incubation phase, an innovation I developed to ensure both a dense biomass and a preserved cellulose microstructure.The most critical parameters are oxygenation and nutrient diffusion: the bacterium requires both sugar and oxygen to weave the microfibrils of cellulose. In a static culture, as the biofilm thickens, these exchanges decrease; the lower layers become deprived, and production stops.

The bioreactor helps to overcome this by ensuring gentle mixing, which renews the air and evenly distributes nutrients. I drew inspiration from air-lift and rotary drum systems, where the liquid surface remains continuously exposed to air without disturbing growth. This configuration maintains a balance between agitation and stability: the bacteria remain active, but the structure of the biofilm is not disrupted.

The main drawback of conventional bioreactors is that they tend to alter the microstructure of the cellulose (the microfibrils become more disordered and fragile). I addressed this by combining two growth regimes: a dynamic phase to stimulate biomass production, followed by a static incubation phase to consolidate the matrix. This alternation preserves the density, transparency, and continuity of the biofilm.

In summary, the most decisive parameters are the aeration rate, the geometry of the bioreactor, and the duration of each phase. These variables determine the final form: its density, thickness, and mechanical behavior. Geometry also plays an active role, as it influences the internal dynamics of the medium and the positioning of the cells on the growth surface. Developing this area is challenging because I struggle to find bioengineers who both comprehend my work and possess the skills to assist with the hydrodynamics of shapes.

5. You only made minimal interventions, like flipping or stitching. How do you decide when enough has been done, especially in projects where the organism is the primary maker?

I try to create the conditions for the form to go as far as possible on its own. Even the gestures I still make (such as flipping, stitching, or repositioning) already feel excessive. My goal would be for them to become unnecessary. The real question, then, is not when to intervene, but what to introduce at the beginning so that the system can reach its final form without me.

However, there is always a threshold: the moment when the living system reaches its maximum balance and can no longer evolve without beginning to degrade (a kind of thermodynamic principle). It is this inflection point that often dictates when to stop: when growth ceases and deterioration begins. This judgment is both biological and aesthetic, based on an intimate reading of the kombucha’s metabolism that I have come to know over more than ten years.

Working with an organism means accepting that design also happens through withdrawal. Intervention is no longer an act of control, but a form of listening: sensing when to suspend the gesture and let the material express its own intention.

6. You speak of a “living bioreactor” that invites ethical speculation. If a sourcing tool like Tocco’s included microbial-derived materials, what attributes should it surface? Living status, microbial lineage, care protocols?

My living bioreactor project proposes an unconventional approach to biological cultivation systems. Traditionally, a bioreactor is a control machine: it is used to steer living matter to obtain the desired molecules, enzymes, or biomass. In my case, the question is simple: how can I take care of the bacteria while also making use of their way of living, that is, their ability to form biofilms?

Let’s be honest: I manipulate them to obtain what I want, to grow 3D objects. But through experimentation, I came to understand that the object, the bioreactor, and the bacteria form a single system. If the apparatus is both machine and culture (half bioreactor, half kombucha), then I must also take care of the machine itself: monitoring its humidity, its growth, its balance, as one would with a hybrid organism. This is how we might move beyond the binary logic in which a machine exploits cells, toward an ecology of agencies, where each entity (human, technical, biological) co-depends on the others.

This question is epistemological before it is technical. To understand an organism is to understand a system of assimilation and interaction: how it absorbs, lives, spreads, and reacts to its environment. It is not about separating things but about recognizing the similarities between systems - whether biological, technical, or social.

If a tool like Tocco were to include materials derived from living organisms, it should not only describe their composition but also their conditions of existence. Bacterial cellulose, for example, is not a stable material: it evolves, breathes, and degrades. Its temporality should be made visible, showing how long it remains active, under what conditions it is maintained, and how it transforms. Some designers are moving in that direction, but I remain critical of the bureaucratic tendencies of these approaches.

Beyond the “living status”, the essential question is that of the culture relationship. Where does the strain come from? In what environment did it grow? What practices made its development possible? Nutrients, temperature, water, or even the hand that maintains the culture profoundly influence the final form. There are as many kinds of kombucha as there are people and territories keeping them alive. All these parameters express an implicit ethics, one based on cohabitation rather than exploitation.

Such a tool could therefore make visible attributes that are rarely considered: microbial lineage, material limits, care or neutralization protocols (sterilization, pasteurization, or maintenance, depending on intention). These are not merely technical data, but signs of a shared responsibility toward living matter, and above all, an opening toward the multiplicity of possibilities. I think we tend to valorize only certain directions, while this is precisely about showing that many others exist.

Ultimately, it all depends on the status of this life: do the bacteria remain active within the device, or not? If they do, one must specify their lineage, their physiology, and the care conditions associated with them. But, as in medicine, knowing what heals and what kills remains uncertain. Working with the living means accepting this grey, undefined zone where attention prevails over control.

7. The bacterial cellulose adapts based on its environment. Should responsiveness be considered a material property in future sourcing or certification systems?

I believe that responsiveness should be recognized as a material property in its own right, especially when working with materials derived from living systems. Current certification frameworks value stability, resistance, and neutrality, that is, everything that denies the changing nature of matter. This makes sense, as it ensures safety, durability, and the absence of toxicity. But it has become urgent to rethink our relationship to materiality.

Today, most new composites are designed to meet industrial standards inherited from plastics. We try to create more sustainable materials, yet we encapsulate them in thin polyurethane films to achieve the same performance, lifespan, and mechanical constraints. It is an illusion: we manufacture supposedly “ecological” materials by enclosing them in conditions that do not exist naturally on Earth. If a material cannot disappear, it becomes pollution; it contaminates soils, bodies, and cells. What we call “durability” is often nothing more than an inability to be metabolized by living systems.

Bacterial cellulose, on the other hand, reacts to humidity, light, and pH. It contracts, transforms, and adapts, sometimes by absorbing abiotic elements. These behaviors are not defects but signs of a material vitality. I am not advocating for a new vitalism, but for the integration of living dynamics into our relationship with the world.

The problem is that most biotechnologies remain trapped in a mechanistic vision of life: an industrial model based on cause and effect, where the organism becomes a simple actuator. Yet an organism does not function like a machine. It perceives, it reacts, and it makes decisions according to logics that exceed mere chemical reaction.

Integrating responsiveness into standards would mean redefining the “quality” of a material, no longer in terms of performance or durability, but in terms of dynamic balance: how matter lives with its environment. This would require criteria capable of assessing not stability, but response capacity and reversibility. This is what part of regenerative design seeks to address today, as an extension of life-cycle analysis, but on a broader and more systemic scale.

This also raises ethical questions: what can we reasonably ask of these non-humans? How far can we exploit their responsiveness without reducing their agency to a utilitarian function? And if we choose to do so, how do we invent a counterpart, a form of shared responsibility, in which we remain attentive to the systems we engage? Recognizing responsiveness is not to anthropomorphize, but to acknowledge that materials, too, participate in the common environment we inhabit.

8. As someone growing components rather than assembling them, what kind of supplier relationship do you imagine? Who or what is the supplier in your process?

My work lies at the intersection of research and practice. After several years in the fablab movement, I came to understand how deceptive the dominant vision of production really is. Global supply chains are built on hidden costs: ecological, social, and energetic, which we simply displace elsewhere. We extract, transform, stabilize, and assemble on the other side of the world, within an economy of separation between territories, species, and responsibilities. All of this is made possible by energy that is artificially cheap yet ecologically disastrous.

Working with living matter is quite the opposite. The “supplier” becomes an environment: water, nutrients, temperature, bacteria, and time. These elements co-produce the material within a system of interdependence. The role of the designer is no longer that of a manager of flows, but that of a mediator, someone who cultivates relationships and learns to compose with the environment.

This approach opens the way to local, endemic forms of production, where each territory develops its own “material culture,” shaped by its nutrients, microclimates, and species. Globalization would no longer rely on extraction, but on the distribution of know-how. Instead of exchanging materials or finished products, we could share protocols, recipes, and cultivation conditions.

More importantly, this approach forces us to rethink our relationship to time and production. In the living world, slowness is not a flaw; it is a condition of balance. Some Indigenous Nations of North America, such as the Chinook, used to cut planks directly from the trunks of living trees without ever felling them. The trees remained standing, sometimes after several extractions, and continued to grow. These practices reflected a relationship to life based on continuity and cohabitation: harvesting without destroying, maintaining the cycle. They remind us that destruction is never truly profitable, except in the abstract models of economics.

I am often told that my processes are too slow: two weeks for a controller, one month for a shoe. But let’s put things into perspective. In the cattle leather industry, an animal must be raised for 18 to 24 months (sometimes more, depending on the system). From the removal of the hide to salting, transport, tanning, and finishing, several more months, even up to a year, can pass. This shows that, in reality, my process is not particularly slow; it is simply more restrained. It mobilizes fewer resources, even though I remain partly dependent on the agro-industrial system for sugar, tea, or vinegar. It is not yet perfect, but achieving such systemic coherence is precisely the goal.

From my perspective, the problem is not the time of production, but our inability to perceive it as anything other than a loss. We must rethink the “supplier” as a living partner, a system with which we share conditions of existence, not a resource to be exploited. The future of design will not lie in mass production, but in networked cultivation, local reproducibility, and what I call a “metabolic folklore”: a world where objects are born, decay, and are reborn without leaving behind an ecological debt.

9. Could bacterial cellulose ever scale in applications like wearables or interfaces without losing the intimate, care-based logic that defines it?

This is an essential question. Yes, bacterial cellulose could be produced on a larger scale, and industrial processes for fermentation and biomaterials already exist. It would therefore be technically possible to adapt these infrastructures for applications in interactive interfaces or textiles. But at that scale, we lose what makes the material unique: its slowness, its variability, its deep connection to a specific environment. The risk is to transform a cohabiting organism into a simple resource to be extracted, as we have always done. How can we escape this intellectual dead end that continues to hold us back?

We must abandon the logic of “scalability” as it is understood in industry. Living matter does not multiply, it proliferates, and proliferation is a distributed mode of expansion, not a centralized one. Instead of production concentrated in a few factories, we could imagine networks of local biocultures (workshops, laboratories, or makerspaces) capable of cultivating the material according to their own conditions: nutrients, climate, micro-organisms. This distributed scaling would preserve biological and cultural diversity while meeting concrete production needs. We would shift from a model of scale to a model of propagation, where care is maintained precisely because it is shared. This would allow us to move beyond artificial scarcity and the illusion that everything is equivalent or interchangeable.

This approach would rely on the transmission of protocols rather than the standardization of results. Each biofilm would become a variation of a common gesture. Care, in this case, does not disappear; it changes scale by becoming distributed. The origin of a material could even be identified through its structure: a biofilm, for example, is like a hard drive in the form of a nanocellulose matrix. Everything is contained within it, and its structure reveals its origin or conditions of growth.

We must reweave our relationship with the world, and this requires a genuine hybridization between our technical systems and the living. We could, for example, use waste heat from our infrastructures to sustain and grow bacteria, yeasts, or other organisms. Some industries already do this, particularly in steelworks. The problem is not our technical capacity but our way of thinking about efficiency: we confuse efficiency (doing fast) with efficacy (doing right). We spend enormous amounts of energy transforming what life already knows how to synthesize at ambient temperature, within perfectly integrated metabolic cycles. What are we waiting for to change?

The challenge, then, is not simply to copy life (as biomimicry tends to do) but to understand how to collaborate with it: to design hybrid systems capable of producing without destroying, maintaining without extracting. It is at this scale, between culture and technology, that biofabrication can renew the very idea of industry: a metabolic, living, distributed, and sustainable industry. This is the ecology of care and efficiency that we must now learn to invent.

10. What lessons could industrial designers draw from your approach to biofabrication? Particularly around relinquishing control and designing for emergence?

The main lesson to be drawn from biofabrication is the need to change posture. Industrial design has been built on mastery: to calculate, optimize, and standardize. Working with living matter means accepting that form does not result from a plan, but from an interaction. One no longer designs against matter, but with it.

This requires abandoning the idea that the designer holds the final vision. My role is not to force matter to match an intention, but to create the conditions under which a form can emerge. It is a design of listening, of context, and of temporality. One must learn to observe, to wait, and sometimes to do nothing, which is counterintuitive for a discipline historically oriented toward action and control. Yet paradoxically, one must master before letting go: to understand deeply the dynamics of living systems in order to surrender to them consciously.

This shift also implies a change in values: moving from result to relation. It is no longer the form itself that matters, but the kind of dialogue it enables between humans, organisms, and environments. Failure, variability, and slowness then become tools for design, ways of learning from complexity rather than reducing it.

In the long term, this approach could profoundly renew industrial design (which is why many designers are already diverting machines or turning toward living materials and DIY practices). Rather than seeking to reproduce identically, we could learn to design conditions of emergence: systems capable of adapting, growing, and transforming. The designer would no longer be the one who fabricates objects, but the one who orchestrates living relationships. Forms then become branching structures of potentialities that can be explored by influencing the parameters of a system.

This is where the cybernetic legacy regains its full relevance. Not the mechanistic cybernetics of early control systems, but one of life and interdependence, as envisioned by Gregory Bateson, Francisco Varela, or Lynn Margulis. Margulis, in particular, proposed a profoundly relational view of the living world. With James Lovelock, she contributed to the Gaia hypothesis, in which the Earth itself is understood as a planetary self-regulating system, a network of feedback loops between the biological, the geological, and the atmospheric. From this perspective, each organism is not an isolated unit but a node of exchanges within a fabric of co-evolutions.

To think this way is to shift the conception of control toward that of cohabitation. The designer, in this context, acts as a mediator of these loops: orchestrating interactions and accompanying dynamic equilibriums rather than imposing forms. They become a practitioner of the living, aware that every stable system is a continuous negotiation between opposing forces.

It is also a way to rethink the unfulfilled promise of mass customization that digital industry has long claimed but never achieved. Where Industry 4.0 struggles to make every product unique, living systems do so naturally: they compose with their environment, they adjust, they differ. Perhaps it is time to renounce producing “the same thing” and to learn instead how to design with difference, which is the very signature of the living.

11. How would you want your materials to be classified in a sourcing database? By species, substrate, electrical behaviour, or ethics of cultivation?

The system I use is similar to a rotary drum bioreactor, adapted for the culture of Komagataeibacter xylinum. The most critical parameters are oxygenation and nutrient diffusion: the bacterium requires both sugar and oxygen to weave the microfibrils of cellulose. In a static culture, as the biofilm thickens, these exchanges decrease; the lower layers become deprived, and production stops.

The bioreactor helps to overcome this by ensuring gentle mixing, which renews the air and evenly distributes nutrients. I drew inspiration from air-lift and rotary drum systems, where the liquid surface remains continuously exposed to air without disturbing growth. This configuration maintains a balance between agitation and stability: the bacteria remain active, but the structure of the biofilm is not disrupted.

The main drawback of conventional bioreactors is that they tend to alter the microstructure of the cellulose (the microfibrils become more disordered and fragile). I addressed this by combining two growth regimes: a dynamic phase to stimulate biomass production, followed by a static incubation phase to consolidate the matrix. This alternation preserves the density, transparency, and continuity of the biofilm.

In summary, the most decisive parameters are the aeration rate, the geometry of the bioreactor, and the duration of each phase. These variables determine the final form: its density, thickness, and mechanical behavior. Geometry also plays an active role, as it influences the internal dynamics of the medium and the positioning of the cells on the growth surface.

12. Your work challenges the binary between material and organism. Should sourcing infrastructures begin to reflect this ambiguity, and if so, how?

Yes, our sourcing infrastructures will inevitably have to evolve if we are to account for the ambiguity between matter and organism. Today, everything still relies on a dualist model: matter is seen as inert, and the organism as living. Yet biofabrication, Engineered Living Materials, and synthetic biology blur these boundaries. Bacterial cellulose, for example, is at once a tissue, a medium, and a process; it cannot be reduced to either a material or a being.

At my scale, this ambiguity already manifests itself in practice. Working with living matter means facing an immediate ethical responsibility: where to find resources, how to cultivate them, and under what conditions. In a world still dominated by extractive logics, it is difficult to make without reproducing the same imbalances. My approach is to cultivate environments rather than extract resources, to think of matter as a relationship to be maintained rather than a stock to be consumed.

Our current infrastructures, by contrast, are designed to describe stable and separate entities, while life operates through relations and transformations. Instead of classifying materials, we should document their trajectories: where they come from, how they interact, what they become. An infrastructure suited to the living would not be a database, but a cartography of ecosystems, capable of tracing the exchanges of matter, energy, and care between humans, machines, and organisms.

This transformation is as ethical as it is technical. As long as we classify organisms as resources, we sustain the illusion of their passivity. To reflect this ambiguity would mean acknowledging that a material has its own agency, behavior, and temporality. We would no longer speak of “raw matter”, but of matter in relation.

Design can play a decisive role in this transition. By cultivating rather than manufacturing, it enacts models of cohabitation that could inspire new forms of industrial and scientific organization. It is not simply a matter of adding an “ethics of cultivation” column to a spreadsheet, but of changing the logic entirely: moving from a system of resources to a system of cohabitation, capable of representing the interdependencies between life, technology, and production. It would be a step toward a truly ecological economy: not one of the living as matter, but of the living as partner.